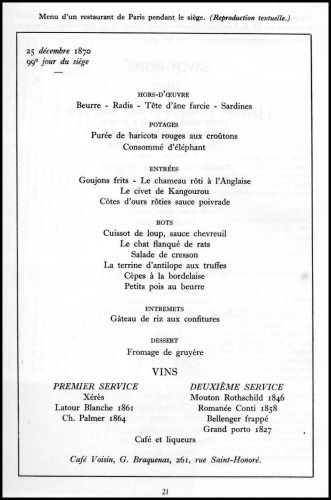

Treatened by Bismark’s growing power and underestimating the growing superiority of Prussian arms and training, the Emperor declared war on Prussia in July of 1870. The conflict was a catastrophe. Battles were lost and villages ravaged. Surrounded, Paris suffered a horrific siege. Bombardment destroyed buildings. Starvation was rife. The zoo and the stables became slaughterhouses. Fine restaurants served rats to their customers—the poorer classes had to catch them on their own.

Class division marred much of the struggle, but many Parisians help one another. The divine Sarah Bernhardt turned the theatre where she worked into a hospital.

The Parisians were trapped and there were few methods of communication. Balloons were used to carry dispatches. An important politician, Leon Gambetta, made his escape from Paris in a balloon.

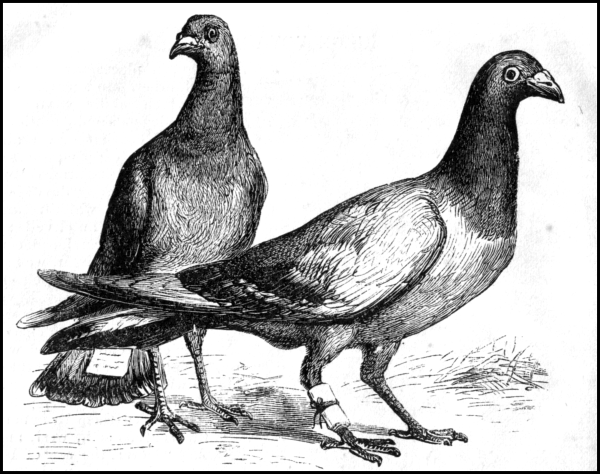

Often they held carrier pigeons to be released later in hopes of bringing back news from outside the city. The pigeons were one of the few successful means of communication during the siege.

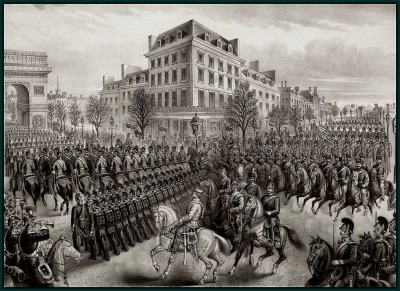

The valiant efforts of the French proved futile. The Emperor was captured by the Prussians and deposed by the new government of the Third Republic. He spent the last years of his life in exile. The new leaders refused moderate Prussian demands and fought on until the accumulation of disasters obliged an unpopular but necessary surrender. The Austrians occupied Paris, now demanding crushing reparations from the country. Through patriotic fundraising efforts, the French eventually managed to pay off what was due and banish the last of the enemy’s troops from Paris.

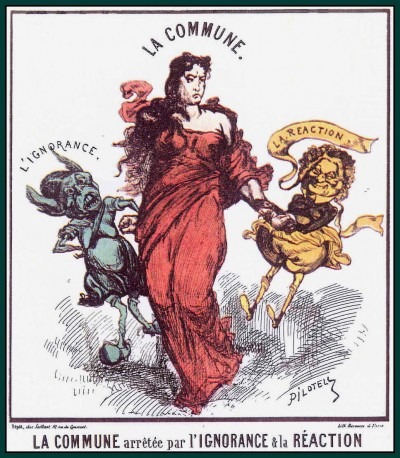

Anger simmered among the entire French populace at their ignominious defeat. The working classes were both furious about the surrender and distrustful of the new regime with its majority of Royalists. The French Revolution had failed to give them any lasting power. The uprisings of 1832 and 1848 had not furthered their cause. Rebellion was stirring once again.

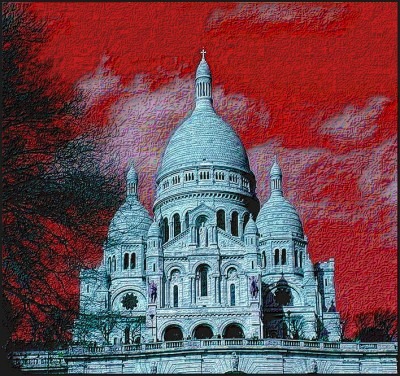

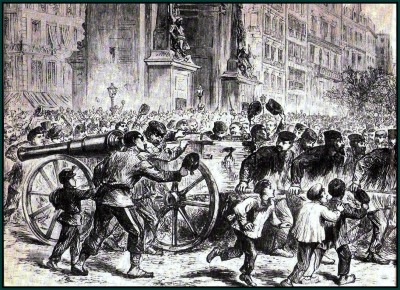

Then the government abandoned the turmoil of Paris for the deceptive calm of Versailles, creating a power vacuum. In Paris, the National Guard still possessed four hundred cannon it deemed belonged to the people, who had provided the funds. The Commune began when Versailles sent orders for the cannon to be reclaimed from the stronghold in Montmartre and elsewhere in Paris. The people would not surrender them. The rebellion had begun.

The people’s revolution spread like wildfire throughout the city, and the remaining troops and many of the police retreated to Versailles. The Central Committee of the National Guard called for elections to form a Commune.

The government troops stationed in the city rebelled along with the citizens and refused to surrender the cannon. Claude Martin Lecomte, the general at Montmartre is said to have ordered his troops to fire on the National Guard and the civilians. Instead he was dragged from his horse and executed along with another officer, General Thomas. Once again, the working class had seized control of Paris.

The Communards believed they were heroes, part of a continuing noble struggle against oppression. But others saw them as villains bent on the destruction of the city they loved.

The Communards were serious in attempting to create a new and, by their own set of liberal and radical ideals, a more just goverment. They tried to maintain and develop the social services of the city. Despite internal differences, the Council made a good start in organizing the public services essential for a city of two million. Bursting with great plans, they published and began to implement a handful of their decrees including the separation of church and state, the end of night work in the city’s bakeries, and the right of employees to claim businesses that had been abandoned by their owners, but granting those owners the right to compensation. Several of these decrees involved the abolition or postponement of debts of various kinds which had devasted the workers during the siege. Tools could be freely reclaimed from pawnshops. Unmarried, as well as married companions of the National Guard, and their children, were to be granted pensions.

Although no specific decrees on women’s rights were implemented, other than the granting of pensions, feminists were very active during the Commune.

Louise Michel was their greatest heroine, who continued the struggle throughout her life, despite long periods of imprisonment and exile. She fought, she wrote, and she brought endless inspiration to others.

Facing the tribunal that threatened to execute her, she said, “It seems that any heart that beats for liberty has no right to anything but a small lump of lead. I demand my share.”

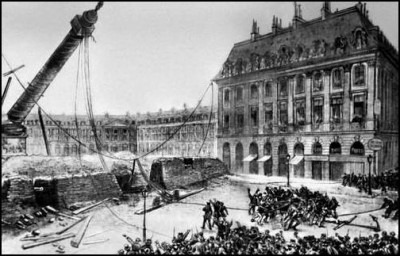

Many of the Commune’s actions were symbolic of destroying the old order. They pulled down the Vendôme column.

They destroyed the guillotine rather than use it for executions.

Perhaps if the Commune had spent less time bickering and more organizing, the outcome would have been different.

Or if, as they’d hoped, their ranks had swelled with soldiers deserting the government in Versailles they might have considered their strategy to hold the city.

But the Communards were not prepared for the invasion of the Versailles troops come to reclaim Paris. The Communards put up barricades as they had in the past. The streets were narrower then, before the Haussmann renovations. Now they dug up the paving stones and gathered the debris from the bombardment of the all too recent war.

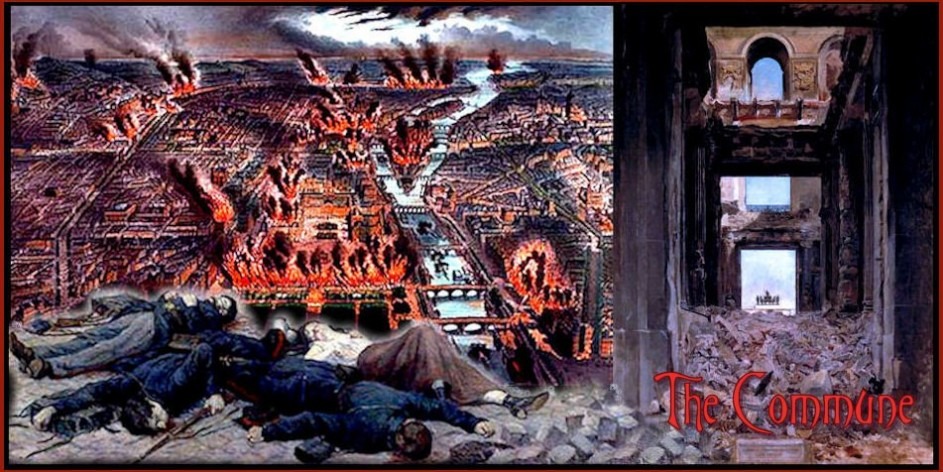

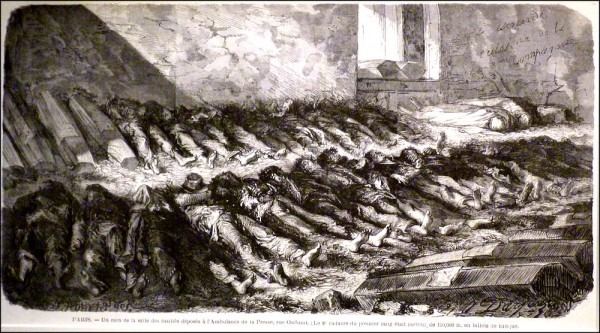

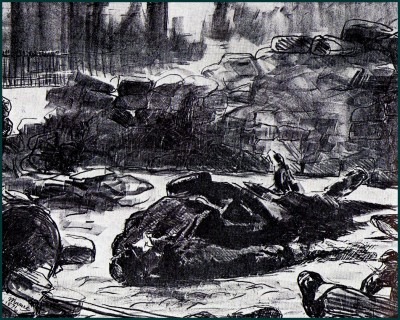

Atrocities were committed on both sides. The Communards had executed many officers, politicians, and even members of the clergy. But the were also many attempts at restraint. Entering Paris, the government troops began a wholesale slaughter that became known as La Semaine Sanglante – The Bloody Week.

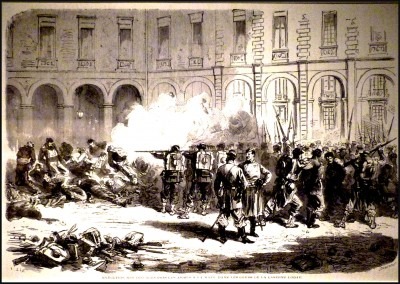

The National Guard and the Communards fought valiantly, but enclave after enclave fell to the government troops. Realizing their dream was doomed, the Communards struck back, attempting to destroy Paris in their rage and despair.

Notre Dame and La Sainte Chapelle were doused in gasoline and saved only by luck. The Tuilleries Palace was burned to the ground, the ruins later replaced by the gardens that we know today. The Hôtel de Ville was destroyed, but rebuilt at great cost to duplicate its former glory.

The battle for Paris ended in Père Lachaise cemetery. The song Cherry Time became an emblem of that lost hope.

Approximately twenty thousand people were executed during the year of the Reign of Terror. During Bloody Week, twently thousand or more Communards – men, women, and children – were slaughtered in the streets or executed without trial.

Thousands more were imprisoned or deported. Many survivors fled into exile. Pretending not to be French, some men joined the Foreign Legion. A decade passed before those who escaped began to return.

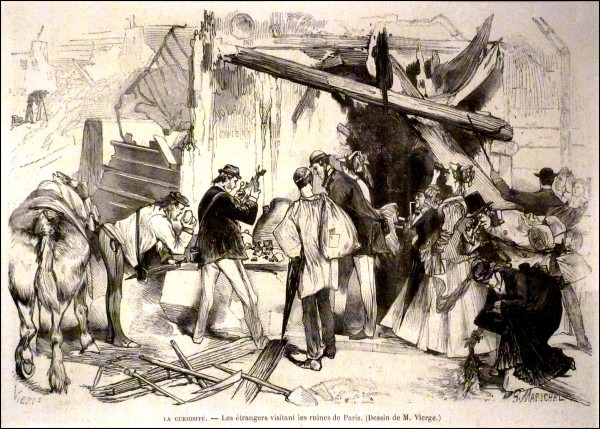

Slowly, Paris began to return to normal. Curious tourists came to view the significant sites of the conflict.

It became linked in the minds of the Montmartroise with the bloodshed and oppression.

Ever since the fall of the Commune, memorials have been held and tributes have been left in Pere Lachaise Cemetery…