WOMEN ARTISTS

I’ll begin with two women successful before the Impressionist era. First, though a bit later in time is Marie-Denise Villers. Little exists of her work today, but one famous painting survives, which was long attributed to Jacques-Louis David, with whom she studied.We know that many of the women in her family trained as portraitists, that she exhibited at the Paris Salon, and that the man she married, unlike many, supported her art.Her Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes is perhaps more likely to be a self-portrait.

More famous and more prolific was Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. Her elegant work is considered to combine a Rococo palette with a more severe Neoclassical style.

Vigée Le Brun’s talent allowed her to become a member of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. She was dangerously successful, as she became a portraitist for the Ancien Régime and Marie Antoinette in particular. She had to flee Paris during the Revolution and traveled throughout Europe for a dozen years, still painting the rich and famous, and being awarded membership in yet another academy in yet another country. She was finally permitted to return to France, but remained devoted to the old order until her death.

There were amusing scandals about her daring-for-the-day art, such as painting a portrait revealing her teeth when she smiled, and occasionally showing too much skin in her portraits and being forced to extend the coverage of a sleeve, or in the case of Marie Antoinette, painting her in her favorite gamboling attire—not at all appropriate for royalty. Vigée Le Brun did an almost identical painting in proper satin and lace. See the shocking version below.

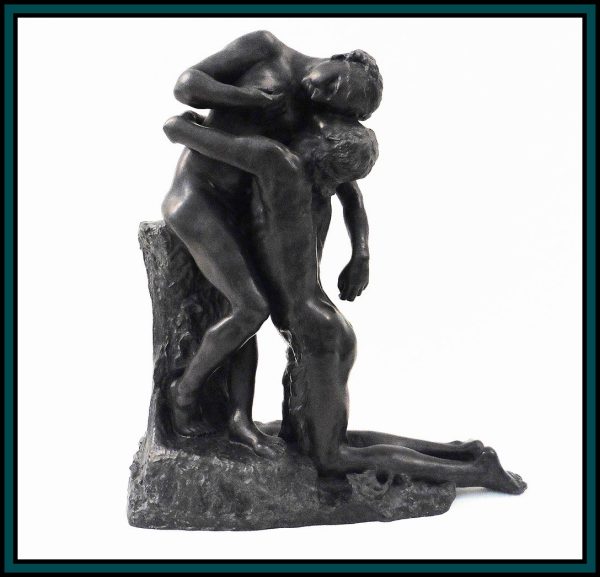

Those two women were exceptions to society’s rules. Everyone has heard of the ubiquitous female artist, Anonymous. Most creative women had their work claimed by fathers, brothers, husbands–and mentors. For centuries, both women and men who served as apprentices were pleased when their work was deemed worthy enough to be signed by the master. Camille Claudel’s sculpture is now recognized as equal in greatness to Rodin, her mentor and lover.

Claudel’s life is tragic, her relative success early in her career, when Rodin still offered his support descends into bitter calamity when Rodin, perhaps threatened by her brilliance withdrew his help, both financial and emotional. After her caring father’s death, her vindictive family confined her to a mental institution. There was evidence of paranoia, but year after year the doctors said she should be released and returned to the world. Her family refused. She was shut away for forty years.

Women’s painting was devalued because they were assumed inferior to men. Their opportunities, their lives, were constrained by society, and then they were criticized for their lack of scope. As a sop, they were considered to have a better eye for detail, for the minutiae of daily life, but to lack the metal acuity to present the grand idea. Domestic arts such as embroidery were promoted as more feminine hobby than painting, and if women did want to be amateurs, the softer mediums, watercolor and pastel were encouraged as more feminine than oils.

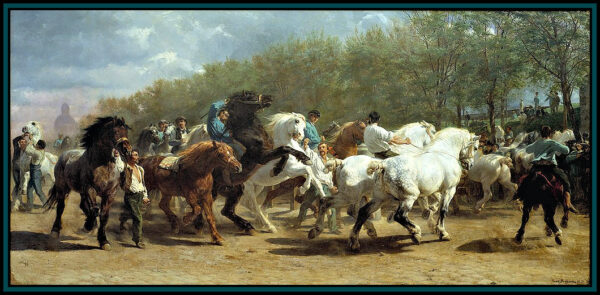

One famous exception was Rosa Bonheur, a lesbian artist who defied the mores of her era and triumphed because of the success of her extraordinary animal paintings and sculptures. Her most famous work is the dynamic oil The Horse Fair, a favorite painting of Queen Victoria’s. Bonheur was granted apermission de travestissement, so that she could wear men’s clothes around the stockyards. In Bitter Draughts, Theo is taken to the police station for daring to defy the law by wearing trousers.

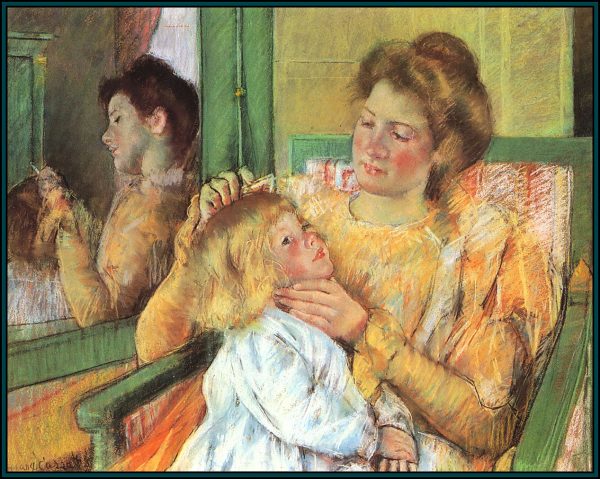

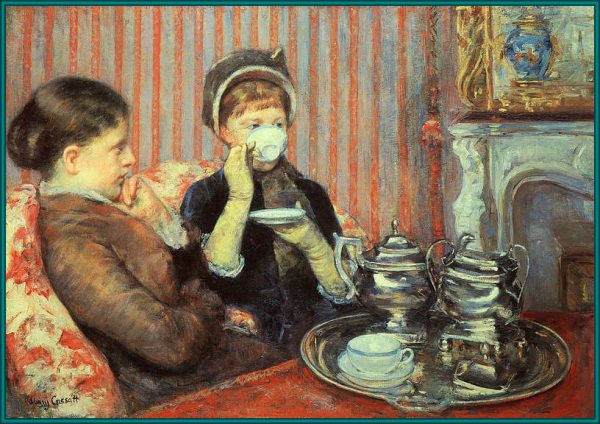

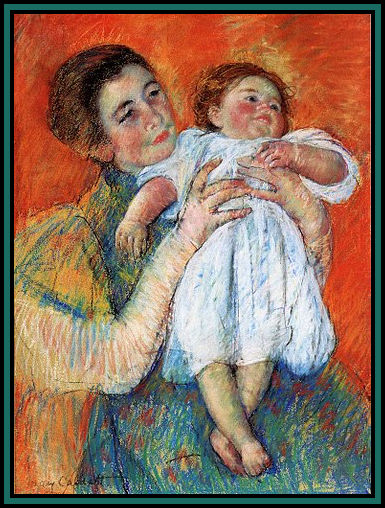

American painter Mary Cassatt is the most well-known woman Impressionist. Her work was championed by Degas, who became a life-long friend. She lived in Paris for decades and exhibited with the Impressionists, but in the 1870s and 80s, it was still improper for her to sit and chat with them in the cafes.

Cassatt did not defy the rules of society but her warm but honest depictions of mothers and children undercut the cloying Victorian ideal. It was a quiet revolution for this was the first time the ordinary lives of women was treated as high art.

It was a confined world, but Cassatt created vivid paintings from domestic and social situations.

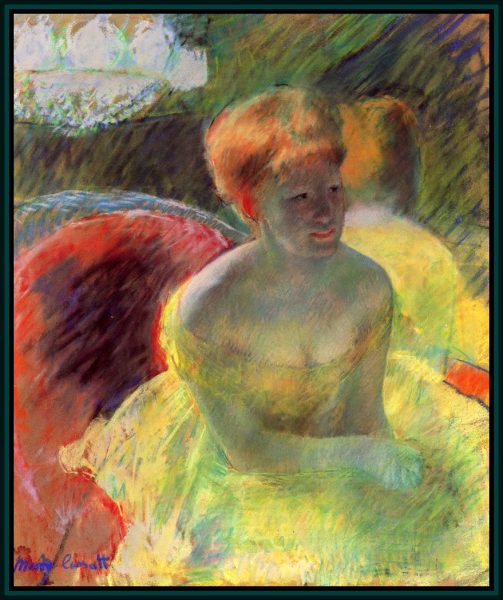

Aside from painting her family members and the friends who came to visit, she painted images of the theatre, one of the few places she could go, properly accompanied. The vivid image below, At the Theatre, displays her command of pastels, a medium in which she excelled.

Today, in Paris you can visit the famed shop where she and other masters of pastel bought the best, the richest version of these exquisite sticks of pure color. Click the image below to learn more.

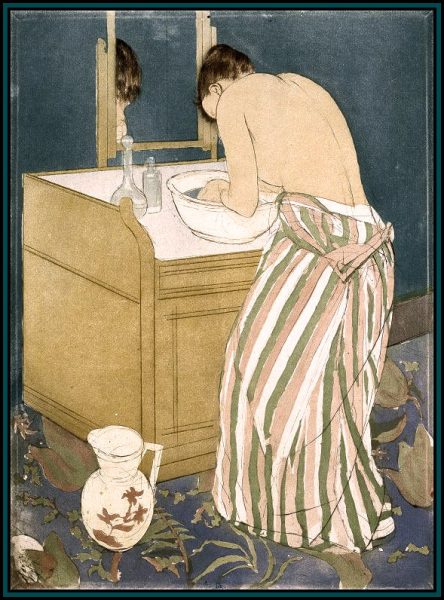

She also explored the world of printmaking, influenced by Japanese art as many of her contemporaries were.

She also explored the world of printmaking, influenced by Japanese art as many of her contemporaries were.

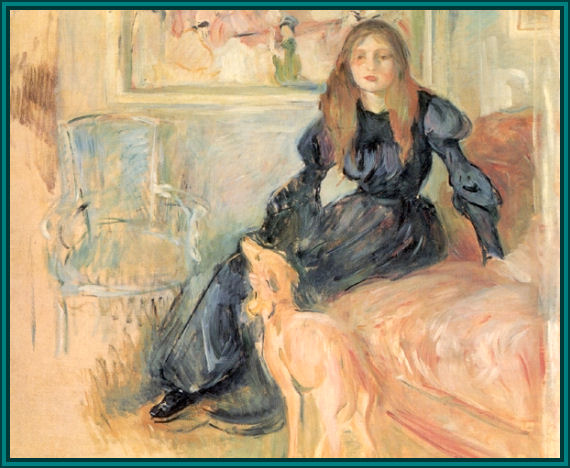

Another marvelous Impressionist artist was Berthe Morisot. Like many of the daughters of bourgeois families, she studied art. Her work was exceptional enough that she showed work in the famed Paris salons until she was drawn to the rising Impressionist movement. She exchanged innovative ideas and techniques with Manet. She married Manet’s brother and, like Mary Cassatt, painted mostly domestic settings.

Some of her loveliest work depicts her daughter, Julie.

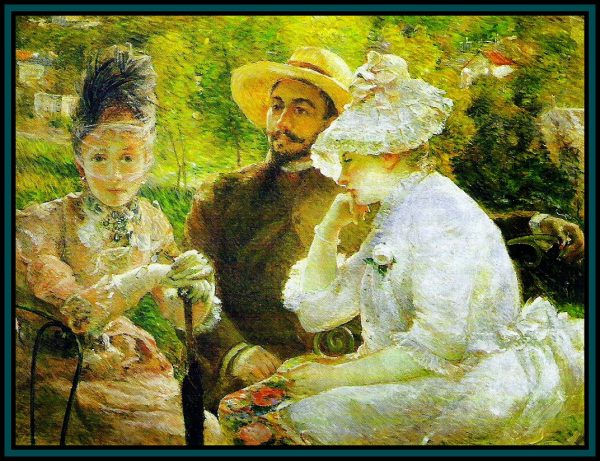

Also born to a well to do family, Eva Gonzalès began studying in a more detailed, classical style.

But after meeting Manet, who took her on as his sole student, her style shifted and became looser.

Like Morisot and Cassatt, her subjects were limited to the enclosed world of bourgeois women, though I found this amusing portrait of a lady taking a donkey ride.

I love the distinctive work of Marie Bracquemond, though we have only a few paintings. Born to a more working class family than the previous Impressionists, she still received early training and began in a more classical style as a student of Ingres. Distrustful of a woman’s ability to sustain the creative impulse, he limited the subjects she could paint. Her talent did lead to early successes and commissions.

She met her artist husband Félix Bracquemond, when she was copying old masters in the Louvre. But her work evolved, while he held to his previous beliefs. Rather than support her artistic endeavors, he because a destructive influence in her career when she found inspiration in the work of the Impressionists.

Her husband despised the Impressionist technique and demanded she abandon it.

Depression and ill health crushed her output, but she continued to defend Impressionism because it offered new ways of perceiving the world, like opening the window to let in a rush of air and sunlight.

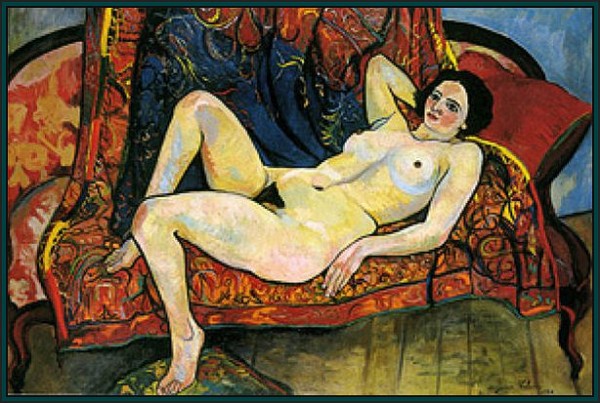

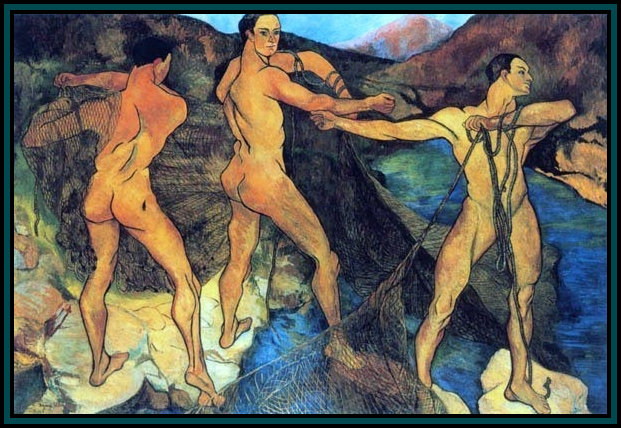

A favorite rebel is the powerful artist, Suzanne Valadon. Born the daughter of a laundress, Valadon was first a circus acrobat.

After injuring herself, she modeled for all the prominent male Impressionists of the day, becoming friends and lovers with many of them. Determined to become an artist herself, she learned from them, especially from Lautrec and Degas, becoming a dynamic painter in her own right. Her nudes are particularly compelling, bold and sensuous without being glamorized.

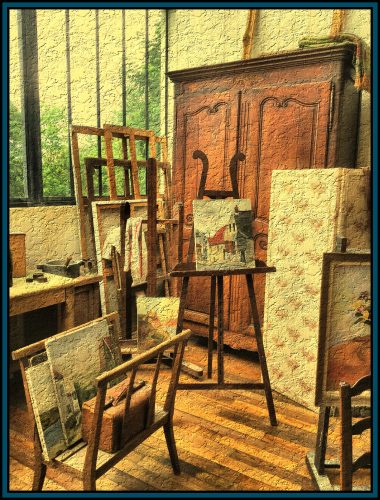

Valadon had her own studio in Montmartre, which has been restored for visitors.

Valadon’s troubled son, Utrillo, became far more famous. He was, after all, male. Valadon was a unique talent, still underappreciated.

Theo is a student at the Académie Julien, one of the top schools for painting in Paris, which happily accepted women in their classes – simply charging them double for the privilege of attending. Most women and foreign students trained in such painting academies or joined professional artists’ ateliers.

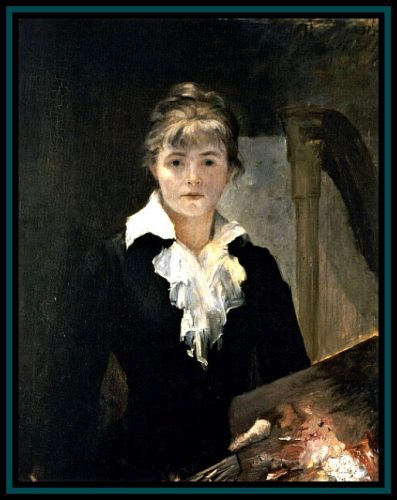

One fascinating student was Marie Bashkirtseff, a Ukrainian painter and sculptor who studied in Paris a decade before Theo arrived. By then, Bashkirtseff was already dead of of tuberculosis at 25–leaving behind a large body of work (sadly, most were destroyed by the Nazis in WWII). Her tomb in the Cimetière de Passy is now a historic monument. It contains a life sized studio.

She also left behind an extraordinary diary of her struggles as an early feminist, entitled I Am The Most Interesting Book Of All.

Although the salon refused to award her any prizes for her exceptional work, she was recognized and applauded by her peers and the public.

Many of her thoughtful portraits survive.

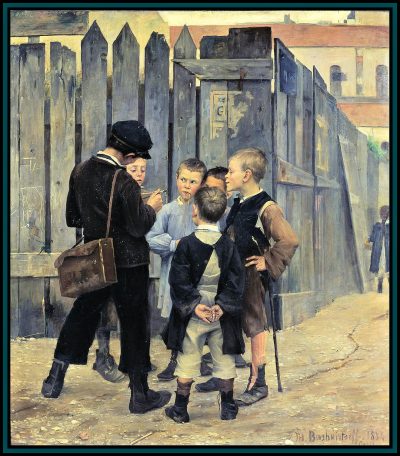

After becoming friends, perhaps lovers, with the Naturalist painter Jules Bastien-Lepage, her work began to investigate social issues.

Bashkirtseff’s The Meeting

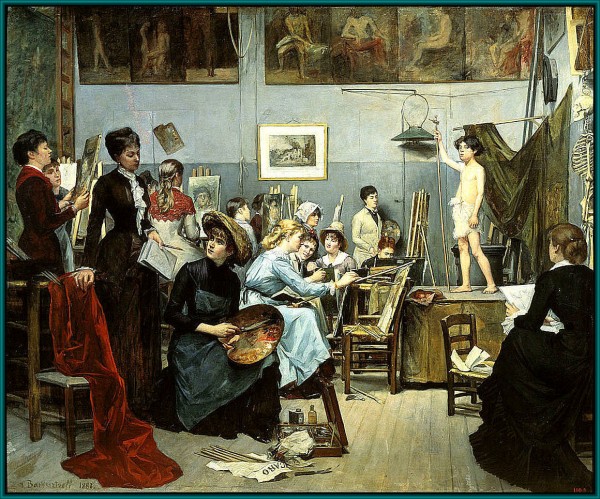

Here is her famous painting of the women’s studio at the Académie Julien,

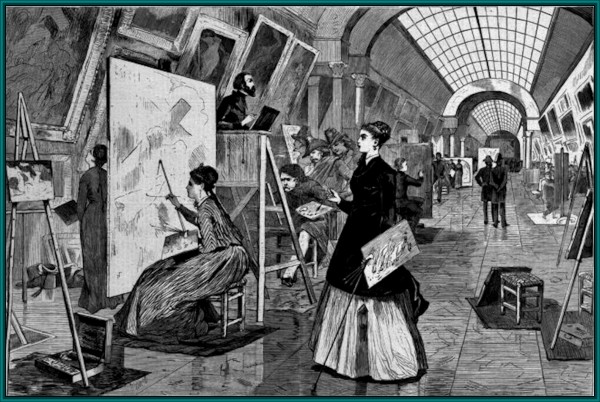

Part of any artist’s education would be the study of the old masters. This is a wood engraving by Winsolow Homer, showing several women copying paintings in the Louvre.

At the Académie, Theo would also learn from the leading contemporary innovators. Many students preferred the academies because they were more open to experimental techniques, but some students attended them only to increase their proficiency before applying to the famous École des Beaux Arts.

Photograph by Dalbera from Wikimedia Commons.

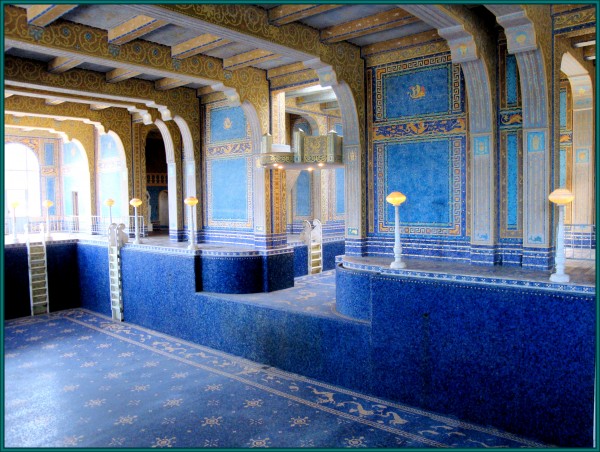

Until the year of my novel, women were not admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts–quite a handsome building as you can see in this recent photo by Hermann Wendler. When the Beaux Arts did allow a couple of women into its hallowed halls, the male students rioted and threw them out in the street. Julia Morgan, the famous American architect who later built Hearst Castle, was struggling to gain admittance to their architectural school–she even has a brief meeting with my heroine on the day of the riots. Unlike the painters, at that time, there was no greater place for architects to study. She was the first woman to get a degree in engineering from the University of California at Berkeley, and the first woman to graduate from the École des Beaux Arts. They did their best to keep her out, but her excellence and determination triumphed.

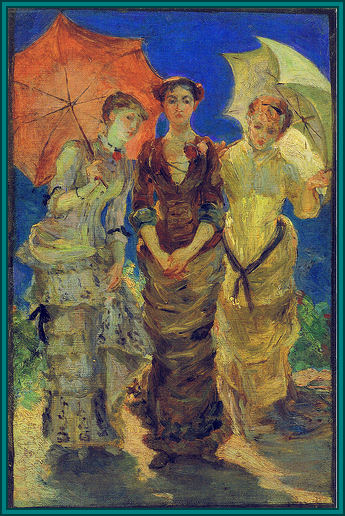

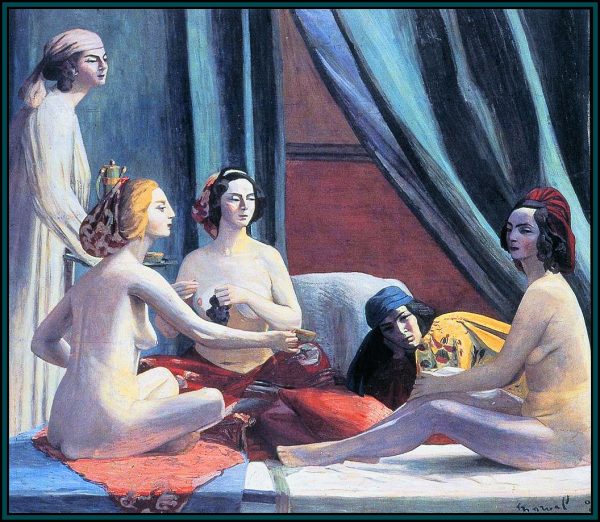

Another rebel is Jacqueline Marval, who began a more sedate life, teaching as her academic parents wished, marrying and bearing a son. But art drew her to Paris, to lovers, and a relatively successful career early in the 20th century.

Les Coquettes

Les Coquettes

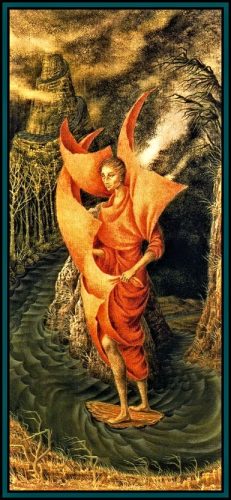

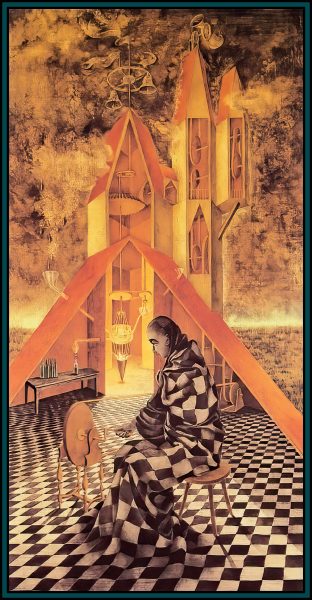

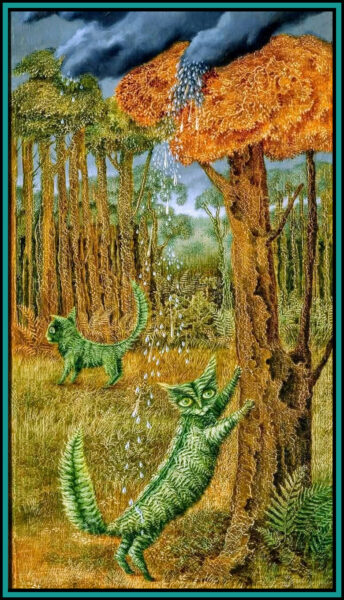

Last but anything but least, my beloved visionary Remedios Varo, who was fascinated with magic and alchemy. She lived in Paris in the Thirties, exhibiting with the Surrealists.

A political activist, she could not return to her native Spain, and in turn fled Paris for Mexico when the Nazis invaded. Little of her work is available to show here. The first images are set in a public space and so public domain.

This appeared on Facebook and must be seen!

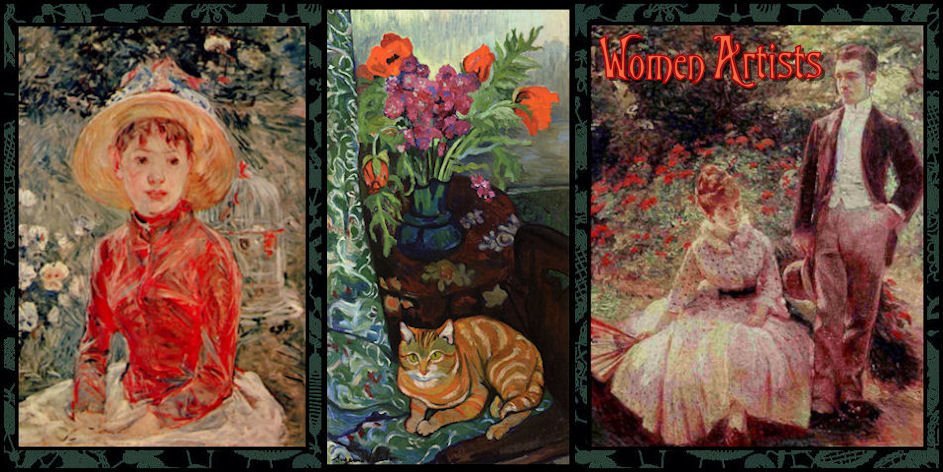

Banner images ~ Mary Cassatt, Suzanne Valadon, and Marie Braquemond.