Cour-te-san The dictionary says the courtesan or courtezan is a woman who has sex with rich or powerful men in exchange for money.

The courtesan is generally considered to be above the common prostitute, but to have lesser status than a mistress.

The origin of the word is Middle French, courtisane, from northern Italian dialect form of Italian cortigiana, a woman courtier, feminine of cortigiano, courtier, from corte, court, from Latin cohort or cohors. First known use is 1533.

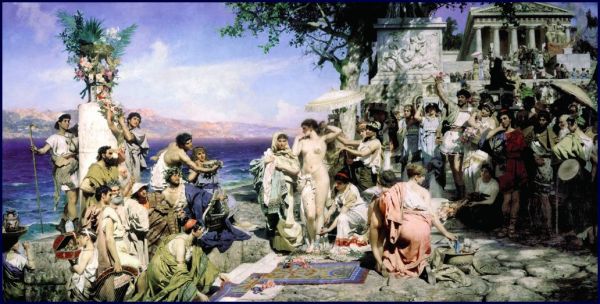

But the role of the courtesan is far older than that word. The Greeks had their hetairai.

They were encouraged to be educated in an era when wives were expected to be all but silent and invisible. Sounds like the Victorian era, too. Sounds like the roles usually assigned women in patriarchies….

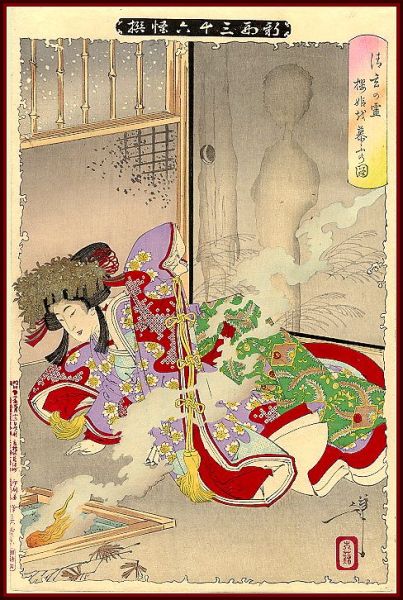

The courtesan has appeared in diverse cultures. Below is the Japanese Geisha, who was trained to be skilled in many arts. The word Geisha can be translated as Artist.

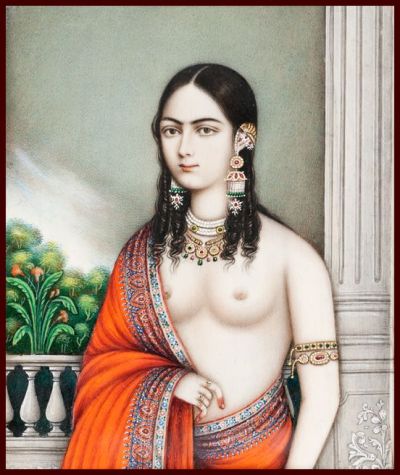

Whatever else they were called, the name courtesan appears to have been widely adopted in current culture.

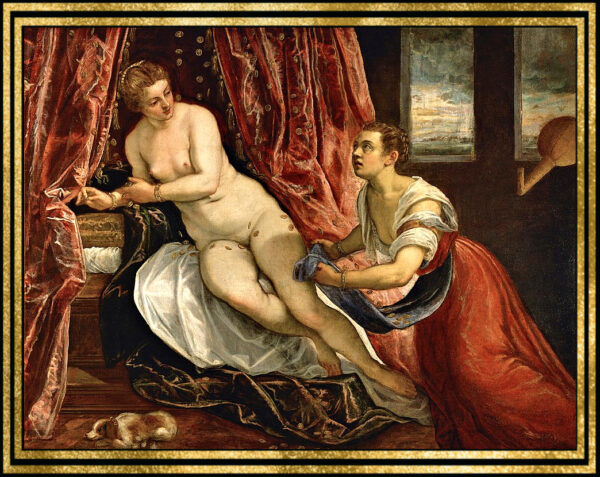

Venetian courtesans had their own golden age. Painted by Tinteretto, here is a painting of one of the most famous, Veronica Franco, whose life inspired the elegant, sensual, and exquisitely costumed film, Dangerous Beauty. Franco was recognized as a poet. She also defended herself ably against charges of witchcraft from the Inquisition.

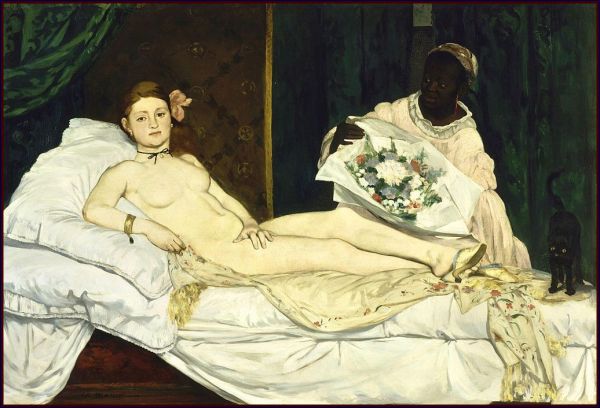

In Nineteenth Century Paris, courtesans were often referred to as Les Grandes Horizontales.

One of my favorite characters in my Belle Époque mystery, Floats the Dark Shadow, is the sharp-witted and sensuous courtesan Lilias Valette. My detective, Inspecteur Devaux, has been having a torrid affair with her for several months.

Going to meet her one night, Michel is struck once again by her deceptive delicacy. Lilias was small, with the fragile, brittle beauty of fine porcelain. She had the bearing and self-possession of an aristocrat. He could picture her at the court of the Ancienne Régime, softly powdered, bewigged, clothed in continents of silk and glittering with jewels. But something raw and ferocious lay hidden below the surface. He could just as easily imagine her carrying the flag through the streets in the Revolution, her feet bathed in blood. Either way, she would be plotting intrigues. It was said that the most successful Parisian courtesans came from the provinces–it took longer to tarnish their innocence. The ones born in the city had an ironic edge that cut into a man’s lust. Perversely, Lilias had triumphed and endured because of that sharpness. Her precision was strangely erotic. Her bitter intelligence and cynicism contrasted with her abandon in the heat of passion. Michel supposed some of her patrons wanted to subjugate that. None had. Though perhaps Lilias offered them the illusion. He would not know. She stirred his desire just as she was.

In researching the courtesans of 19th Century Paris, the customers’ preference for as yet unspoiled young women from the provinces, as opposed to native Parisiannes, was an interesting idea that I encountered. The Golden Age of the Courtesan was waning by the fin de siécle. While France was late in granting women’s rights, it was more sexually indulgent in many ways than contemporaneous countries. As the turn of the century approached, the shop girls were kicking up their heels with more abandon than previously, and the glamorous demi-monde was fading from view.

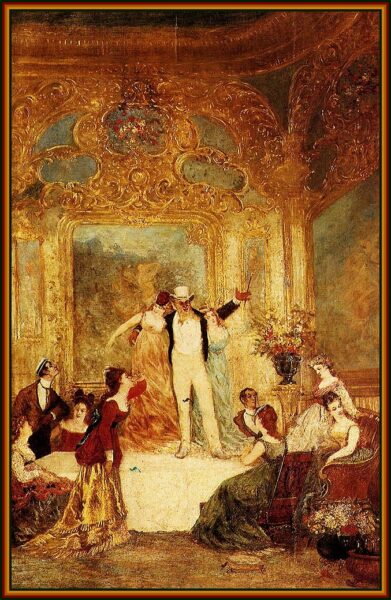

Painting of the salon of another famous courtesan – Une Soireé Chez La Païvia by Monticelli.

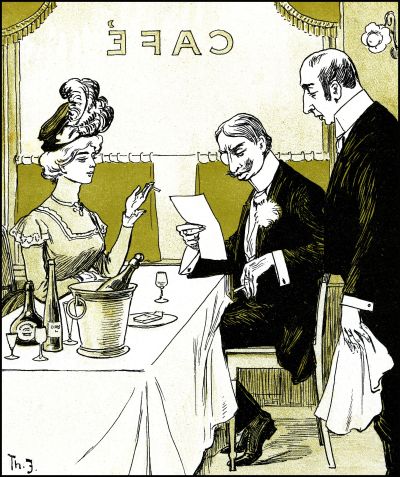

In this cartoon, the waiter protests that none of her other Gentlemen has ever refused the expensive wine the beautiful young woman orders.

Marie Duplessis

Elegant and beautiful women with erotic talent have always been in demand. The epitome of the fresh-faced country girl, not yet made cynical by the wanton life of a courtesan, was the exquisite waif, Marie Duplessis. Like many poor young women, she was sold into prostitution by her family. Like many successful courtesans, she made the best of an ugly beginning by educating herself and transforming from prostitute to courtesan.

Marie is most famous and most appealing of the courtesans who inhabited the Parisian demi-monde because one of her renowned lovers, Alexandre Dumas, fils, immortalized her as the golden-hearted Margeurite Gautier in La Dame Aux Camellias. Julie Kavanagh, author of The Girl Who Loved Camellias, says that she found florists’ records indicating that Duplessis was indeed enamored of camellias.

If you’ve never seen the lovely old tear-jerker, Camille, with Greta Garbo and Robert Taylor, it’s worth watching for her ravishing performance.

Baz Luhrmann usurped a good deal of the plot for Satine’s story in his musical, Moulin Rouge. Both fictional versions of the original die young of consumption. Marie Duplessis did not have even a decade of notorious glory as the most desirable woman in Paris before she died of tuberculosis at twenty-three. If that is indeed what killed her, for her doctor was supposedly dosing her with a concoction laden with strychnine.

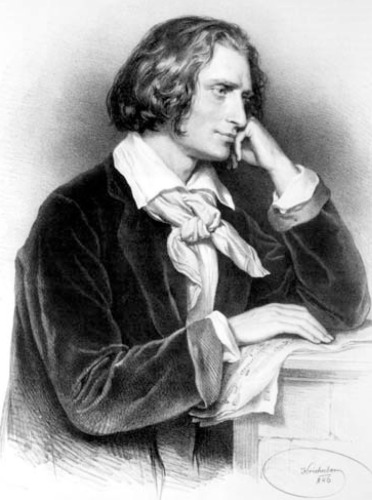

This same doctor claimed to be the one who introduced her to the man who is now her most famous lover, Franz List. He was as much of a celebrity as she was at the time, the equivalent of a rock star, with enamored fans battling for any memento to be had of his romantic performances. The rather modern term, Lisztomania, was coined by Heinrich Heine in 1844 after watching Liszt’s performance sends his fans into a sort of mystical ecstasy.

Liszt may or may not have been the great love of Marie Duplessis’ life. She did beg him to take her away with him when he left for Constantinople. He promised to return, but lingered, caught up in his own career. He was still abroad when news came to him of her death. He is quoted as saying, “I do not know what strange, mournful note vibrates in my heart at the memory of her.”

List wrote that she had an enchanting nature, and the that the corrupting life she lived did not touch her soul. Certainly, her image conveys innocence, and her contemporaries all seemed, to some extent, to echo Liszt’s view, though Duplessis was addicted to luxury and easily bored, a fragile butterfly aware of her own doom.

Cora Pearl

Marie’s main rival in this era was Cora Pearl. After a misadventure where she was seduced, drugged, and abandoned, she seized her fate and worked her way up from prostitute to fabled courtesan.

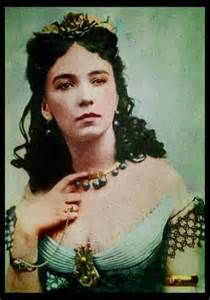

Tinted image of Cora Pearl.

It struck me that she resembles Jennifer Jones, the first American actress to portray Madame Bovary, Flaubert’s sadly infamous heroine who relieved the boredom of her provincial life by flinging herself headlong into amorous affairs in a futile search for love.

Cora Pearl had a long and flamboyant career that included serving herself up nude on a silver platter, dying her hair to match the lemon yellow interior of her carriage, and collecting a million dollars in jeweled tribute to her charms.

In the film, Gigi, from Colette’s famous novelette, naïve Gigi is warned by her fabled courtesan grand-aunt never to accept theatrical jewels. Fabergé would certainly be preferred to Lalique. Fabulous jewelry, an extravagant wardrobe, carriages, a furnished town house, and lavish parties paid for by the protector would all be expected benefits for the courtesan.

Cora Pearl toppled abruptly from the pinnacle of her success. The same sort of scandal could seemingly make or break a courtesan’s career depending on when it occurred. In this case, a younger lover she’d impoverished sought her out with a gun. Perhaps she was the intended victim, but he decided instead to turn the weapon on himself. The wound was almost fatal, and although he finally recovered, the scandal ruined her reputation, and she was ordered to leave France. Like the later beauty, La Belle Otero, Cora Pearl gambled away the remains of her vast fortune and died in poverty.

Much of their early history is known, and I’ve referred to these women as prostitutes, but this is a misnomer for most of the famous courtesans. They may have walked the streets, but they were never arrested and forced to take on that blighted name. French prostitutes were highly regulated. Being officially entered in the system was a stigma they likely would not have escaped. According to George Drysdale, in his Victorian study, The Elements of Social Science: “On the contrary, the woman, who does not court notoriety, but admits few lovers and in secret, although she receives money, cannot, and dare not, under penalty of damages for libel, be called a prostitute. This distinction is in Paris of great importance, for the police of that city exercise a surveillance over all the public prostitutes, who are obliged to enroll themselves in a registry, to receive sanitary visits &c., while they have no control over any other women. Hence the numbers, habits of life, and destiny of the prostitutes are much better known in Paris, than in any other city.”

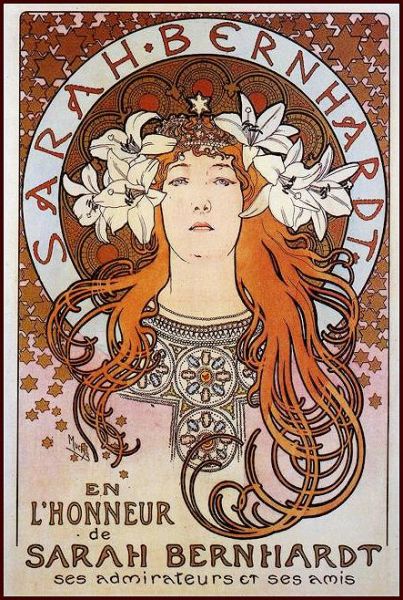

I won’t detail Cora Pearl’s affairs here. Instead, I’ll briefly present the three of the most famous beauties of the Belle Époque. These are not women like Sarah Bernhardt or Coco Chanel, who were courtesans or mistresses to wealthy men. Although all three of these women performed in the theatre, they were primarily known for their affairs and their desirability.

Liane de Pougy

Cartoon probably of, or possibly drawn by, Liane de Pougy, called L’art d’Être Jolie.

Liane de Pougy was born Anne Marie Chassaigne. Raised in a nunnery, she rebelled and ran off at sixteen with a naval officer, Armand Pourpe. She was pregnant and he did marry her, but Anne Marie had no talent for motherhood. Baffled by her little boy, she was even unhappier in her relationship with her husband, who proved physically abusive. She bore a scar on her breast from his beating. She took a lover, a marquis, and when Armand discovered them in bed he shot her. Fortunately, the bullet only struck her wrist. Anne Marie managed to escape to Paris by selling their piano for 400 francs. After a tawdry beginning on the streets, she found a mentor, Madame Valtesse de la Bigne, and began her career as a high-priced courtesan. Anne-Marie developed a skillful conversation about painting, books and poetry, but avoided seeming too erudite for fear she would be boring.

While the general image of the courtesan suggests a woman of some wit and learning, it was not necessarily the case, the protagonist of Emile Zola’s Nana was certainly crass.

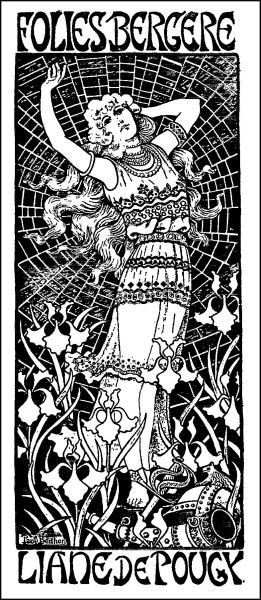

Anne Marie’s career was quite successful, and she became a chorus girl at the Folies-Bergere, renaming herself Liane de Pougy after one of her lovers, the Vicomte de Pougy.

She was a ravishing beauty but had no acting talent, at least according to Sarah Bernhardt, who attempted to coach her at one point, but is quoted as suggesting Liane keep her mouth shut while on stage. Liane had an elegant figure and appears quite graceful in her photographs. She makes a brief appearance in Bitter Draughts, coming to aTheo’s gallery opening with Lilias Valette.

Soon after my fictional event, Liane had an affair with the American heiress and poet, Natalie Clifford Barney, who held literary salons in Paris for many decades.

This daring duo may find a way into another book in my series. Liane wrote her own novel about this, entitled Idylle Saphique. Barney dressed as a Renaissance page and sought out Liane, declaring herself to be a “page of love.” Liane also played the page on occasion.

Natalie Barney tried to convince Liane to abandon what she considered a demeaning profession, but Liane was proud of her role as one of Paris’ premier courtesans and thought it a silly suggestion. But Liane did eventually end her career–by marrying a prince and becoming Princess Ghika. The prince eventually deserted her, but they did not divorce. Her son’s death as an aviator in World War I turned Liane towards religion and she became Sister Anne-Mary, a tertiary of the Order of Saint Dominic. At the Asylum of Saint Agnes, she helped with the care of children born with birth defects.

La Belle Otéro

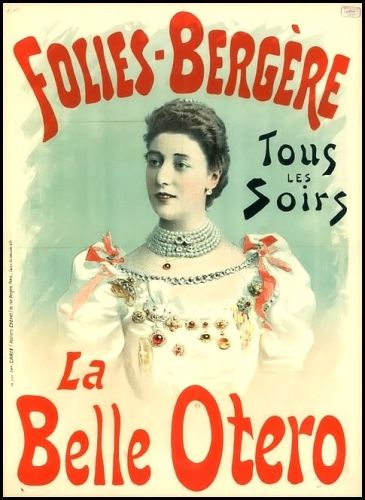

Drawing of La Belle Otéro by Leo Rauth. Click the image to see a few seconds of her dancing.

La Belle Otéro was born to poverty in Spain. Like Marie Duplessis before her, Augustina Otéro Inglesis was raped as a child. Like Marie, she disregarded her painful past as best she could. She worked as a singer and dancer in Lisbon but had her eye on fame in Paris. Using her lovers as stepping-stones, she came first to Barcelona, then Marseille, where she renamed herself La Belle Otero and created a gypsy legend for her character. Soon La Belle Otéro was a star of the Folies Bergère in Paris.

For years she was the most sought after woman in Europe, with dukes, princes, and kings numbered among her many lovers. It is rumored that men committed suicide for her, and that duels were fought. One of the more amusing legends associated with her is that the twin cupolas of the Hotel Carlton in Cannes were modeled on her voluptuous breasts.

Like many other famous courtesans, La Belle Otéro acquired a vast fortune. Hers was estimated at a quarter of a million dollars. Like many others, she pined for her glory days and could not find happiness when her beauty faded. She gambled away her fortune, bemoaned her lost youth, and died in poverty near the casinos in Monte Carlo.

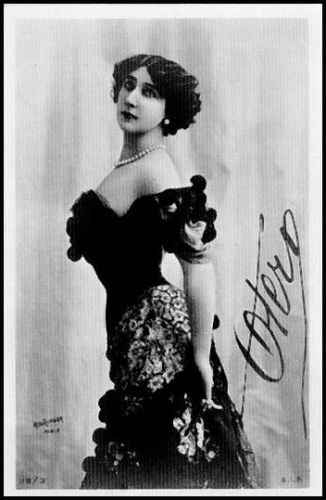

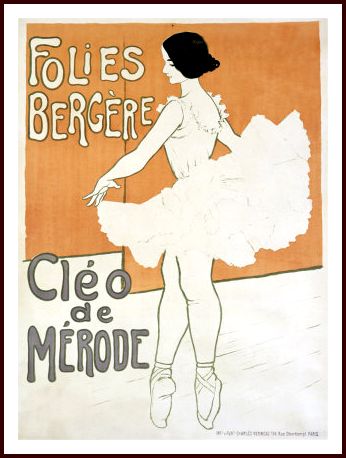

Cléo de Mérode

The last beauty I’m including was a dancer whose real name, rather fantastically, was Cléopatra Diane de Mérode. She claimed in her autobiography, La Danse de ma Vie (The Ballet of My Life), that she was not a courtesan and had only two great loves. As the poster above shows, she dared to dance at the Folies-Bergère, a move which only increased her popularity–and her notoriety.

To me, her image conjures the perfect Hippie princess and couldn’t resist including her. She did dance as a ballerina, a career that began in childhood and continued on throughout her life, but it is still her beauty that is most admired. There was a scandal associated with her, as the aging King Leopold II of Belgium saw her dance and became smitten. The rumor mills conjured an affair that damaged her reputation as a dancer, though she was nonetheless an international success.

It’s easy to imagine her playing Juliet.

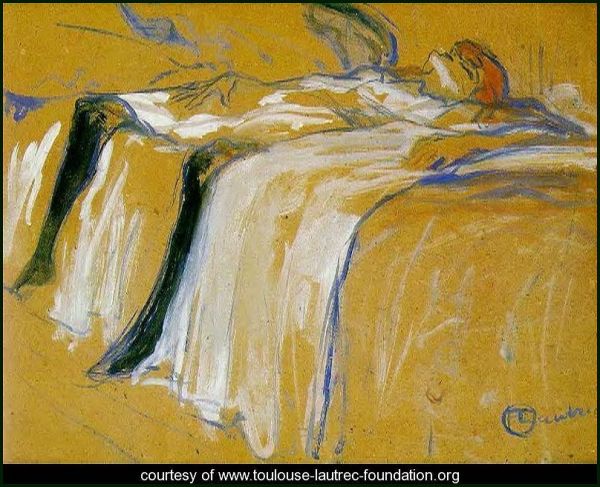

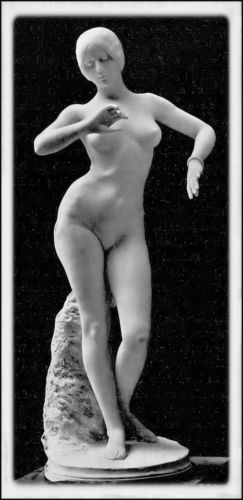

Her beauty inspired many artists, Toulouse-Lautrec and Gustav Klimt among others. A statue of her by the sculptor Alexandre Alexandre Falguière may be seen in the Orsay Museum in Paris.

Her personal style was copied avidly. Here she appears in the mutton-legged sleeves that were the epitome of chic the year Floats the Dark Shadow is set.

Another style she popularized is the coiled chignon hairdo shown in this portrait by one of my favorite painters, Giovanni Boldini. She often wore the style with a metal filet around her forehead.

Cléo de Mérode danced into her fifties, wrote her book, and lived on into the 1960s. She is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery, beside her mother.

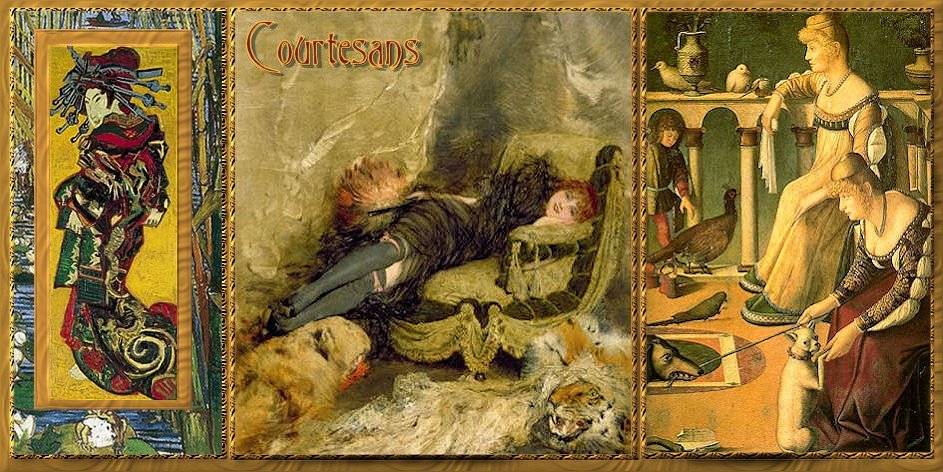

Banner image composed of a detail from Van Gogh, The Courtesan by Jan Van Beers, and Two Venetian Ladies by Carpaccio.