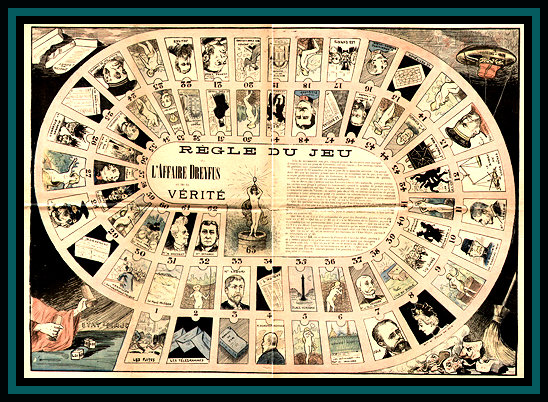

The Dreyfus Affair was called the Scandal of the Century for almost that long. It’s a tale of treachery, incompetence and corruption that will echo far longer than a hundred years.

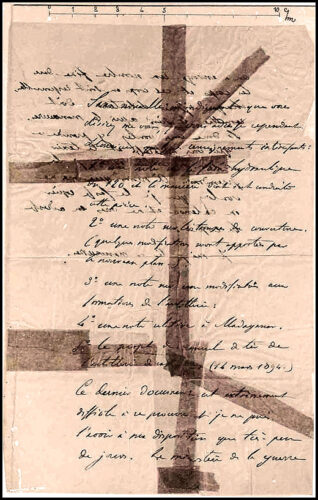

It all began with the bordereau. In the summer of 1984, cleaning lady and French spy Marie Bastian discovered this torn memorandum in the wastepaper basket of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, military attaché at the German Embassy in Paris. This thin piece of paper was ruled in squares and covered on both sides with handwriting. It contained secret military information, including information about a special 120-millimeter cannon that the French were developing. Marie Bastian sent the compromising document to the French Counterintelligence Office.

Major Hubert-Joseph Henry noticed the bordereau was written in French and began to hunt for a spy withing the ranks. As well as the canon, the bordereau mentioned a firing manual for the field artillery and modifications to artillery formations. After much conjecture and ill-founded assumption, the examining Army officials decided the spy had to be an artillery officer. Choosing from among these, they decided the traitor must be Captain Alfred Dreyfus because, well, you could not trust a Jew, especially a Jew originally from Alsace-Lorriane–under German rule since the humiliating Franco-Prussian war. If Dreyfus’ record was unblemished except for having too high an opinion of himself for a Jew, well, the record must be wrong. Besides, his cursive handwriting had a slant a little like the handwriting in the bordereau.

In October of 1894 Dreyfus was arrested and jailed on charges of high treason and questioned avidly for weeks.

His chief interrogator, Commandant du Paty du Clam, was greatly disappointed when Dreyfus did not quail, crumble, and confess when asked to copy lines from the bordereau. His handwriting was tested numerous times, in numerous fashions. It did not match the bordereau if he wrote with his right hand, with his left, not even if he was made to wear gloves. One, then another, handwriting expert declared that yes, quite right, Dreyfus’ penmanship does not match. Therefore the bordereau was not written by Dreyfus.

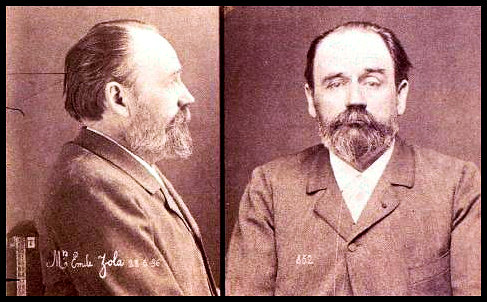

Another expert in criminal detection, the famous Bertillon, was summoned. Bertillon had advanced many new means of detection and preservation of evidence, such as taking photos of crime scenes as evidence, and creating combined side and frontal mug shots of criminals for the records. His complicated method of criminal identification through hard bone measurement had been adopted in many countries.

But Bertillon scorned ideas put forward by others. The new art or fingerprinting for example, he distrusted. Likewise, Bertillon had no faith in handwriting analysis. But he understood from the Army that Dreyfus was guilty and had no problem presenting the theory that Dreyfus had produced an “auto-forgery,” cleverly disguising his own handwriting to escape discovery.

Ironically, famed author Emile Zola, defender of Dreyfus, once posed for a Bertillon mug shot.

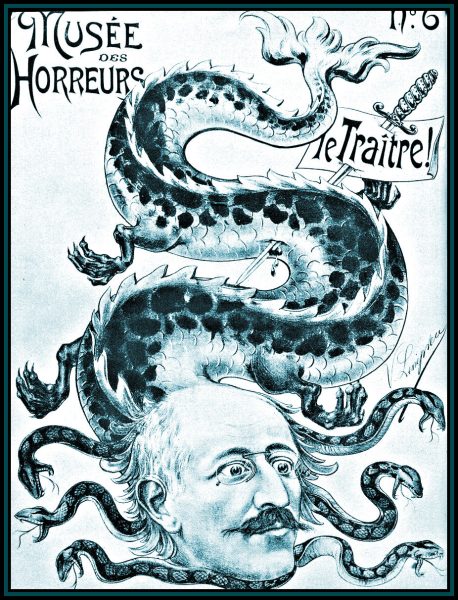

Dreyfus refused to confess to the trumped-up charges. Not all the handwriting experts would proclaim him the author of the bordereau. Realizing their evidence was feeble, the Army decided to improve upon it. Far better to falsify documents than let a traitor escape. Major Hubert-Joseph Henry assembled a “secret dossier” from real and forged communications with Schwartzkoppen, none of which had originally involved Dreyfus but now implicated him. One note mentions a scoundrel indentified as “D.”

In December of 1894, Dreyfus was court martialed. The secret dossier was never brought forward in evidence in the courtroom. Neither Dreyfus nor his lawyer knew of its existence. Instead it was given to the judges to convince them of Dreyfus’ guilt, with warnings of its top secret status. Despite his protestations of innocence and the literally flimsy proof presented in court, Dreyfus was convicted of high treason. The death penalty for treason during peacetime had been abolished and instead he was sentenced to permanent deportation–solitary confinement for life on Devil’s Island.

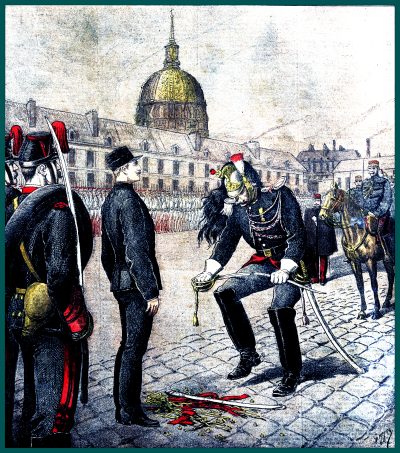

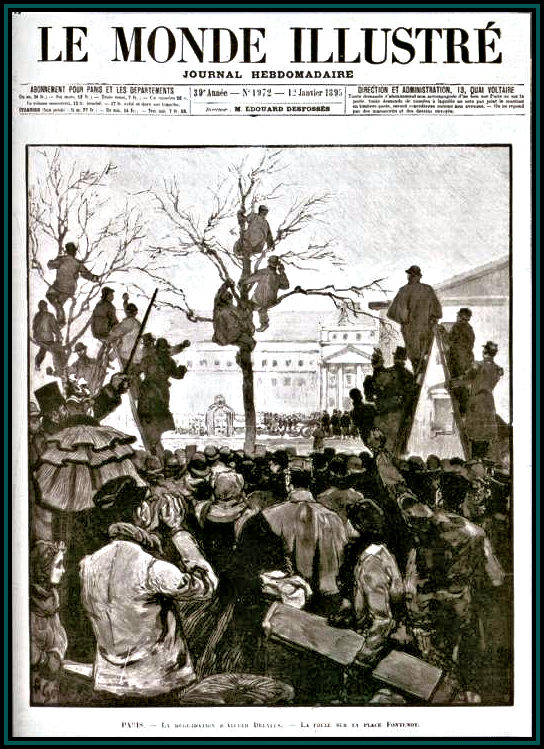

On January 5th, 1895, Dreyfus was subjected to a ceremony of degradation at the École Militaire in Paris. His epaulettes were torn from his uniform and his sword broken.

He was then paraded before the crowd to chants of “Death to Judas,” “Death to the Jews.”

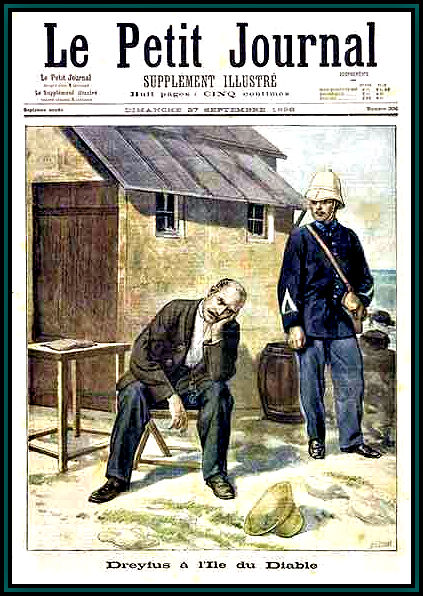

In April of 1895, Dreyfus arrived on Devil’s Island.

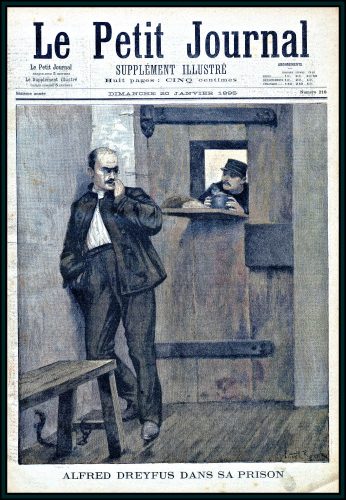

Devil’s Island, off the coast of French Guiana, was first a leper colony, then a prison for political offenders. No one escaped the island for the encircling sharks enjoyed a frequent dinner of dead prisoners and live ones would be even tastier. The death rate from disease and abuse had been horrifically high and the island prison had been closed down. It was decided to reopen it specifically to house the abominable traitor.

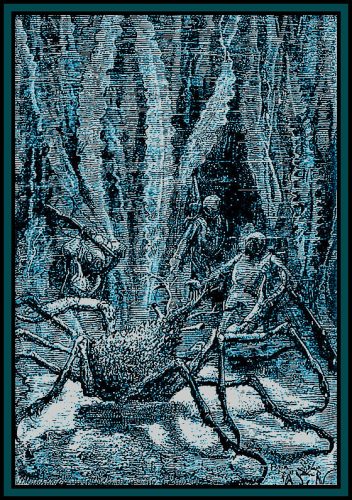

Dreyfus was fed rotten food. He was guarded by men forbidden to converse with him. The temperature was often over 100 degrees but he had no shower. After a false report of his escape circulated in the European newspapers, Dreyfus was moved to a different stone hut shut behind a palisade that blocked his view of the sea. For the next two months he was shackled to his bed at night. Along with the ever-present plague of mosquitoes, his nighttime invaders included army ants and spider crabs.

Dreyfus’ health plummeted. He suffered from malaria, dysentery, and a form of brain fever. To remain sane, Dreyfus studied literature–translating Shakespeare–and mathematics. He wrote to his family and to the government of France, pleading his case. His correspondence was heavily censored, and he remained unaware of the campaign to proof his innocence that slowly gained ground over the next few years.

Dreyfus’ wife, Lucie, and his brother, Mathieu, protested his innocence. At first they were stonewalled at every turn. They were not entirely alone, but the majority of France believed the Army would not convict an innocent man of treason. There must have been piles of evidence.

One of the earliest turning points is censored in the history books, because the accusation of the Army holding back “secret documents” came from a psychic. By a circuitous path, Mathieu Dreyfus learned from a mutual friend that Dr. Gilbert, a doctor in Le Havre, had told the new, more liberal President of France, Félix Faure, that his brother was innocent. Gilbert’s belief comes from experiments he’s conducted with the clairvoyant, Léonie Leboulanger.

Not wanting to ignore any possibility, Mathieu Dreyfus went to visit them. He found a wrinkled peasant woman sitting on a couch, her eyes closed. She looked far older than her 50 years, her face framed with a Norman bonnet. The doctor told him to sit in front of her and when he did, she took hold of his thumbs, moving them this way and that, scratching lightly at his skin. Speaking slowly, she told him a little about his family and his journey–and that his brother suffers greatly. Then she rises and seems to speak directly to his brother, asking why he is wearing glasses.

Mathieu Dreyfus then assumed she was a fake. His brother never wore glasses only a monocle. Léonie insisted, but he left disillusioned. Soon after, Lucie Dreyfus received word that her husband broke his monocle and was now wearing glasses. Mathieu Dreyfus then returned to Léonie and from her learned that there were secret documents shown only to the judges. He began the quest for validation.

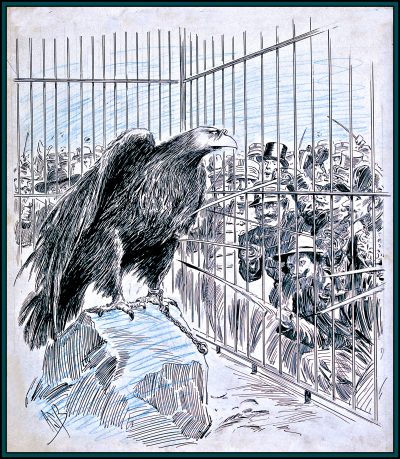

Meanwhile, within the Army, Lieutenant-Colonel Georges Picquart became the new Director of the Statistics Section at the Ministry of War. Although he personally disliked Dreyfus and Jews in general, he had a strong code of honor. He’d been told to bolster the case against the Jew, but after examining the handwriting of the bordereau and the secret dossier used to convict Dreyfus, he became convinced that Dreyfus was not the real spy and began to investigate further. Eventually, Picquart discovered the “petit bleu” a telegram that was never sent, written by von Schwarzkoppen and addressed to a French officer, Major Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy. Other documents emerged, including letters penned by Esterhazy which exactly matched the handwriting of the bordereau. Esterhazy used to be in counterintelligence. A gambler and a womanizer, his reputation was already in tatters and he was deeply in debt. Unlike patriotic Alfred Dreyfus, he despised the French Army.

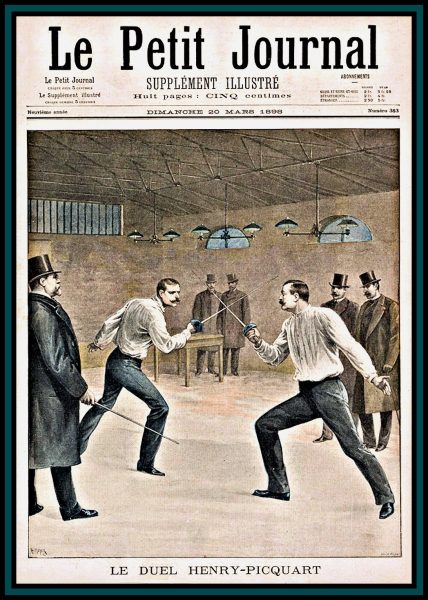

Picquart brought forward his proof to his deputies and his superiors but, as with the Dreyfus family, his efforts were thwarted at every turn. Some officials in the Army refused to believe the proof. Others insisted that Dreyfus should endure his false accusation of treason and heinous imprisonment to protect the reputation of the Army. His credibility was undermined and he was even challenged to a duel by Major Henry. He scored twice against his opponent.

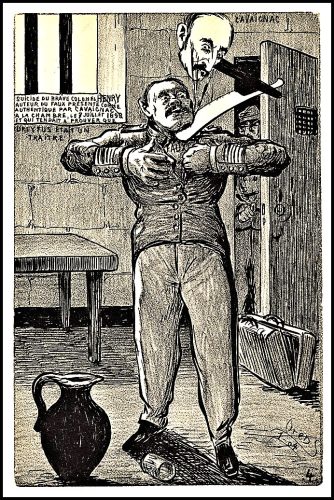

After an investigation into Major Henry’s involvement in l’Affair, he confessed to his forgeries. Confined to a prison cell he either committed suicide or was murdered in August 1898. As usual, the Right proclaimed him a hero and blamed Dreyfus for his death.

Fearful of Picquart’s knowledge, the Army sent him on a life-threatening mission to Tunisia. He survived and grew more committed than ever to seeing Dreyfus freed and Esterhazy convicted.

The Dreyfus family’s petitions and appeals to the authorities were at first fruitless, despite the ever-growing accumulation of evidence against the Army, but things were beginning to change. More and more authorities within the government and influential people without joined their cause. The most significant was the renowned novelist, Emile Zola, who began a campaign of public letters addressed to the people of France. Furor grew with each new missive and on January 13, 1898, he published his defense of Dreyfus in an open letter to the president of France, the famous: “I Accuse!”

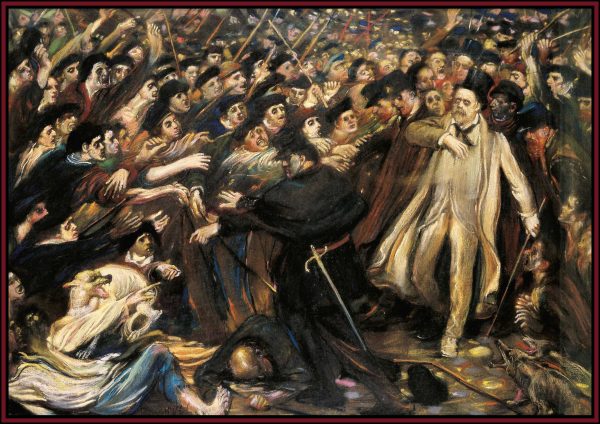

Riots broke out all over Paris, and across France and its colonies. His writings had inflamed the anti-Dreyfusards and his life was threatened.

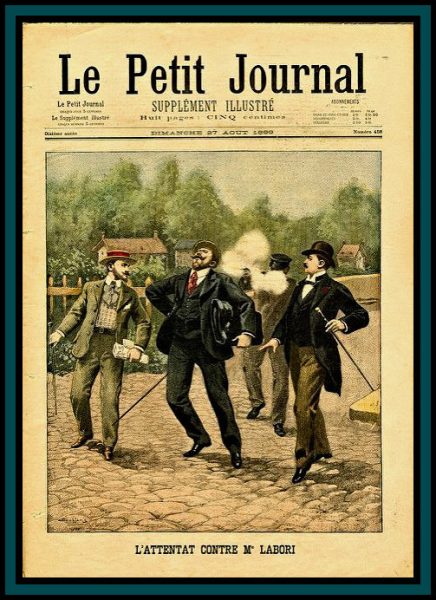

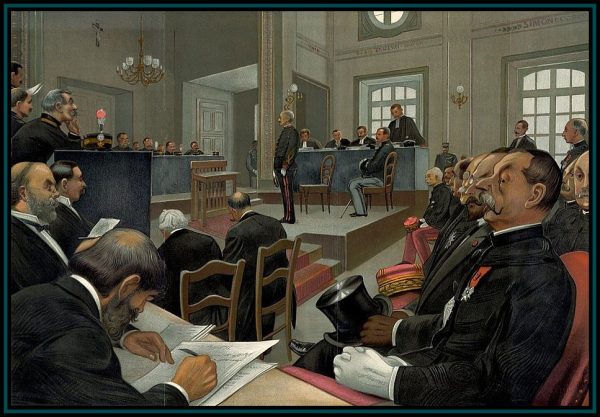

Almost immediately, Zola was put on trial for criminal libel, mocked and jeered in the courtroom. In Bitter Draughts, his assassination is planned. In actual history, his lawyer was shot in the back on the way to defend him.

Reporters from all over the world gathered for the circus of a trial. The London Times noted: “Zola’s true crime has been in daring to rise to defend the truth and civil liberty…for that courageous defense of the primordial rights of the citizen, he will be honored wherever men have souls that are free….”

The evidence at the trial proved that Dreyfus was innocent, that Esterhazy was the traitor. It was obvious that the military had conspired to cover up the truth. Nonetheless, Zola was convicted and sentenced to the maximum penalty of a year in jail. Unwilling to endure prison, he fled to England for a year. Like Dreyfus, he was vilified by the Anti-Dreyfusards.

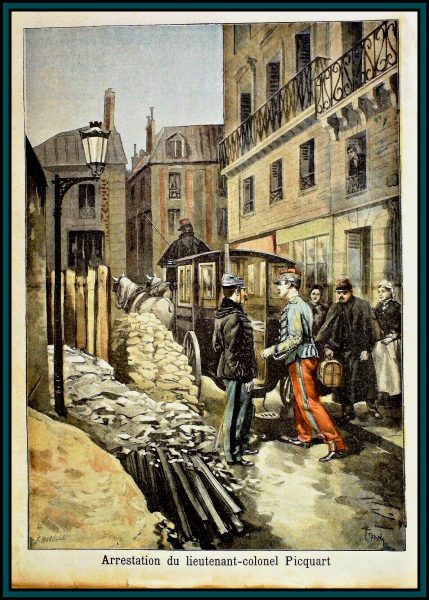

In turn, Picquart was arrested on various charges, such as writing the bordereau himself and revealing military secrets. Brought before a board of enquiry, he was “discharged for gross misconduct in the service” and imprisoned for several months.

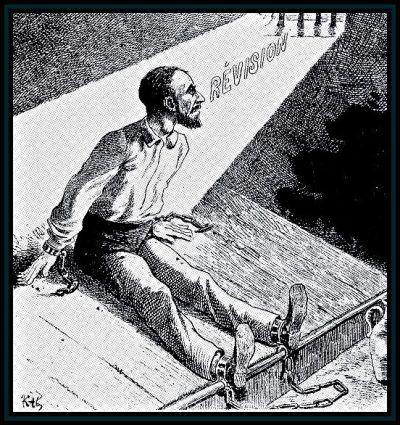

But public outcry was having an effect. The Court of Cassation overturned the 1894 verdict against Dreyfus and ordered a new court martial. Captain Dreyfus was shipped back to France from Devil’s Island and transferred to the military prison in Rennes. Yet, despite the overwhelming evidence in his favor, the judges and the public would prefer the Army to be innocent and the Jew to be guilty. Dreyfus was found guilty with extenuating circumstances and sentenced to ten years in prison.

However–as a supposed gesture of mercy for his ruined health, Dreyfus was immediately offered a pardon for his crime. Wearied by his sufferings, he reluctantly accepted so that he could return to his family. Soon after, the courts passed an amnesty law pardoning everyone involved in the Dreyfus Affair. The guilty were to remain unpunished. The Dreyfus Affair was an ongoing political game.

It was not until 1906 that Dreyfus’ conviction was overturned and he was ajudged innocent. He was reinstated in the Army, promoted, and awarded the Legion of Honor. He was even blessed with a military parade. Picquart was also exonerated and promoted to brigadier general.

Zola not there to see the final outcome. He’d died four years earlier in his Paris apartment, from carbon monoxide poisoning. There were rags stuffed into his chimney. His death was declared an accident but it may well have been murder. Decades later an Anti-Dreyfusard workman declared on his death bed that he’d deliberately clogged the chimney then unblocked it the next day to avoid detection.

50,000 people came for Zola’s funeral at the Montmartre Cemetery. Fellow artists and government officials paid their respects. Soldiers presented arms as the hearse passed. Dreyfus was there and author Anatole France gave the oration in Zola’s praise.

In 1908 Zola’s remains were exhumed and taken across Paris to be interred in the Pantheon, the honored mausoleum of France’s greatest citizens. But Zola was still loathed by the anti-Dreyfusards, who attacked the hearse during the procession only to be driven back by police. Zola’s coffin was first placed on a towering catafalque within the Pantheon and would later be placed next to the tomb of Victor Hugo. There was an official ceremony the next morning, attended by the President of France, and most of Zola’s family.

Dreyfus also came to pay his respects. As he stood near the tomb, a Right-Wing journalist fired two shots at him, wounding him in the arm before being seized by police. The man was brought to trial–and acquitted.

Unlike Piquart, Dreyfus was refused the rank of general, which he believed he deserved. He retired from the Army but later served in WWI.

Piquart died in 1914 at Aimens. Dreyfus died in Paris in 1935 and was buried in Montparnasse cemetery.

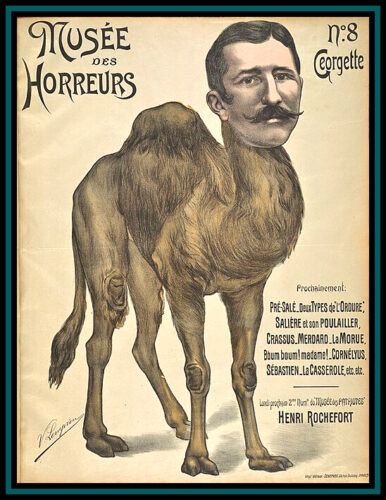

Banner Images: Truth Emerging From The Well by Édouard Debat-Ponsan and L’affaire Dreyfus, La Dernière Dame Voilée, en place pour le quadrille by Henri Gabrielle Ibels.