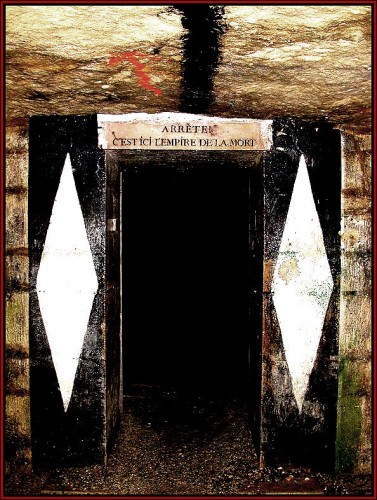

“Arrété! C’est ici l’empire de la mort!”

Halt! This is the empire of death!

So reads the sign greeting visitors at the entrance to Les Catacombes de Paris.

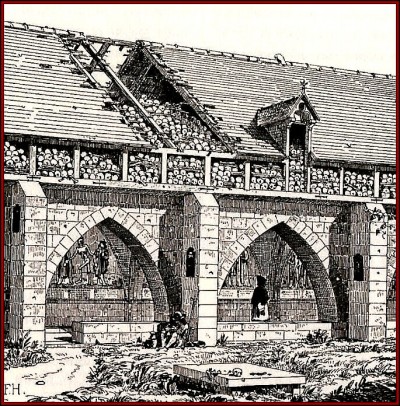

The necropolis of Paris had its birth above ground, in the ancient cemeteries of the city that year by year heaped their dead ever higher above ground. The Cimetière des Innocents was particularly loathsome. It was born as a graveyard in the 4th Century, and breathed its last sigh of corruption in the 18th.

Cemetery of the Innocents by Theodor Hoffbauer

By the end, the fetid stench emanating from the enclosure in the very heart of Paris was infamous. Its mass graves lay open, filled with rotting corpses, until fifteen hundred or so bodies were clasped in its earthy embrace. Only then were the they covered over and another trench begun. Sometimes the putrefying bodies did not sink deeper into the ground, but pushed up higher, breaking through to the surface. So charnel houses were built along the cemetery walls, and bones from the graves packed within them, the walls decorated with a danse macabre. In turn this house of the dead began to decay. After a prolonged rain in the spring of 1780, cracked walls spilled their gruesome contents onto the streets of Paris. Nearby businesses were suffering the ill-effects of this insalubrious spectacle. No one ventured near unless they must. The entire city suffered from epidemics aggravated by the noxious environment at its center.

Even as the King pondered what might be done to improve matters for those living cheek by jowl with the dead, the ancient quarries across the river proffered a solution. Long mined for chalk and the very limestone used to construct the city, the tunnels of these abandoned quarries began caving in and exposing their vast warrens.

The first major collapse occurred along the rue l’Enfer, the street of Hell, in December of 1774. A vast maw opened, claiming several lives along with several houses. As the cave-ins continued to gobble the neighborhood, King Louis XVI commissioned inspectors and architects to examine the problem. As the tunnels were shored up and made safe, inspiration struck. The deceased inhabitants of the Cimetière des Innocents would have a new home. All the bones were to be moved to the abandoned quarries.

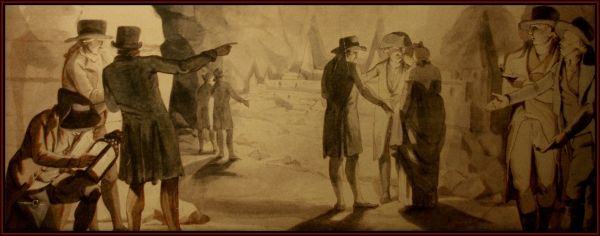

In April of 1786, the exodus began–in the dead of night. En route, priests accompanied the black-veiled remains, chanting a burial service, as they made their way through the streets of Paris. The transport continued even after the overthrow of the monarchy, for the cemeteries continued to be pestilential, and bones from other locations were added to the growing piles, and the property emptied of its former occupants cleaned and renovated.

And so the catacombes of Paris were born.

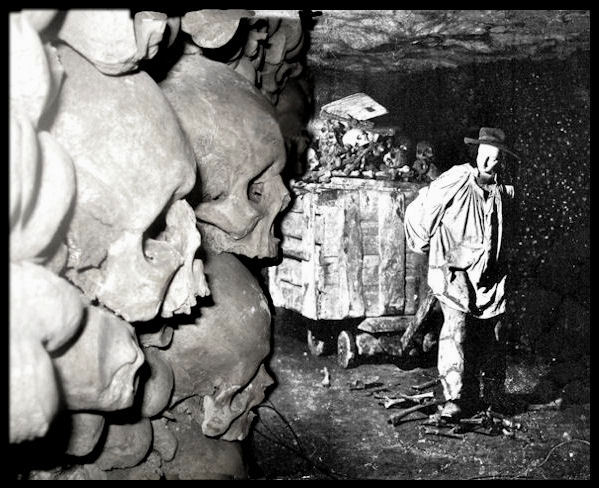

The bodies were exhumed, the bones gathered and transported to their new home.

Some corpses were not completely decomposed. Their remains dissolved into a greasy fat which was collected to be turned into candles and soap (something to be considered to lend authenticity to your next Halloween party).

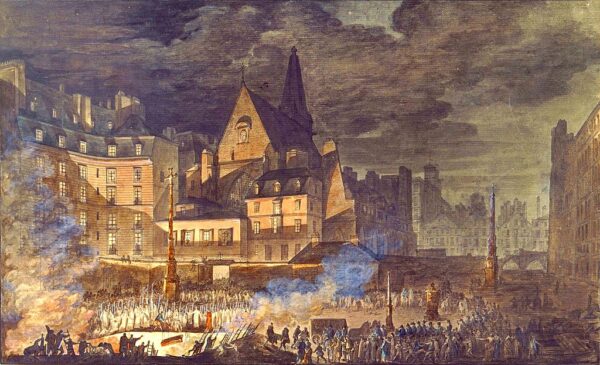

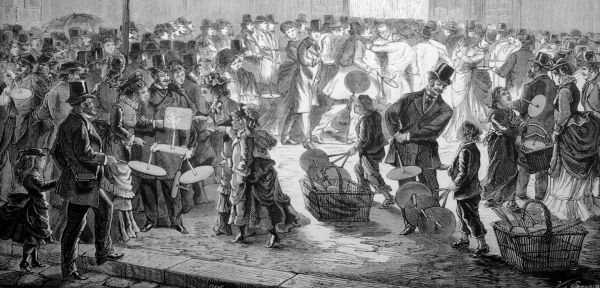

Soon, the former abode of Death transformed into bustling market of Life.

Image by Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer.

For several more decades, the bones were brought to the quarries, filling room after room, but still occupying only a small part of the two hundred miles of subterranean tunnels. The bones of the famous–Danton, Robespierre, and Rabelais–mingled willy-nilly with the anonymous. Over six million skeletons settled into their final refuge beneath the bustling streets of Paris.

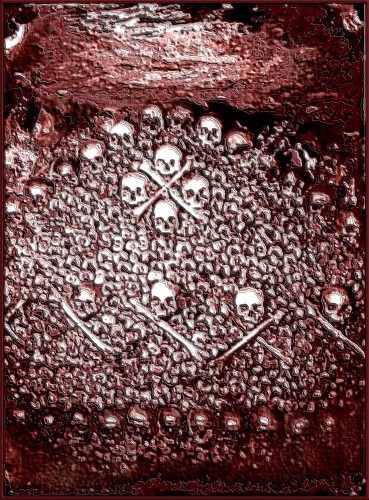

The workmen given the chore of distributing the bones had a macabre sense of humor and the French flair for artistic display. The walls of bones that lined the tunnel hallways were given wave-like rhythms, or punctuated with designs of hearts and crosses created from the skulls.

But the order is pure illusion. Behind the pathways walled with rows of tibia crowned with skulls, are loose heaps of bones several feet deep.

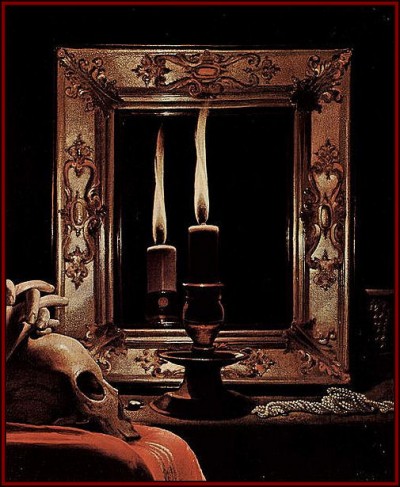

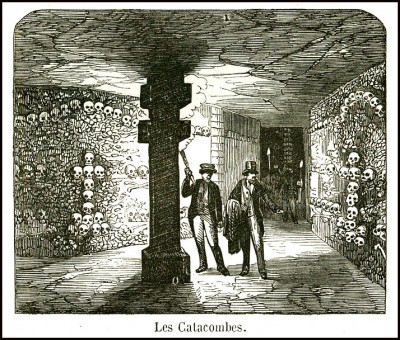

From the very first, the catacombs were a tourist attraction for Parisians and foreigners, commoners and royalty. Here is a strange image of what appears to be a mass candle-lit tour circa 1870.

Even after entry was forbidden, or, perhaps, even more avidly after entry was forbidden, the macabre tunnels became an object of fascination. Guides promised to take visitors to the most secret rooms and midnight concerts were performed in la crypte de la passion. Such a performance is a centerpiece early in Floats the Dark Shadow.

In this buried world, the temperature never varies from its eternal fifty-two degrees. Summer or winter, spring or autumn, a morbid chill permeates the air. Men have strayed and been lost. Even now to enter unguided is to risk death, for the pathways branch off into an ever-darkening labyrinth where explorers could and did get lost and die, eventually adding their bones to the vast ossuary.

Banner created from a photo by Janericloeb.