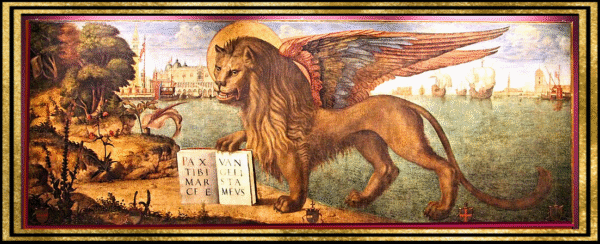

“La Dominante”, “La Serenissima”, “City of Masks”, “City of Bridges”, and “The Floating City” are a few of the names given Venice over the centuries. The Lion of St. Mark is her symbol.

A refuge that became a city of dreams, Venice was built from group of 118 islands linked by 438 bridges that cross the Grand Canal and the lesser canals that weave land and water together. She rests on 10 million pylons of alder and other woods which resist rot in water.

Before there was a city, the islands, the marshy lagoon were home to fishermen. But with the fall of Rome and the endless Germanic and Hun invasions, refugees fled to the safety of these islands because the shallow waters of the lagoon were treacherous to those who did not know their pitfalls. And as the European world grew in strength again, Venice grew as a city, becoming a Republic (a very select Republic), and an unusually stable city state amid the chaos surrounding it. Venice was one of, perhaps, the greatest Medieval power in Europe because of its unrivaled access to trade with the Byzantine empire. It celebrated its maritime and financial prowess until the 16th century, when growing conflicts and the opening of new trade routes ended its supremacy.

Canaletto was one of Venice’s most renowned artists, particularly for his intricate views of the city. Here he showcases a view of the Ducal palace.

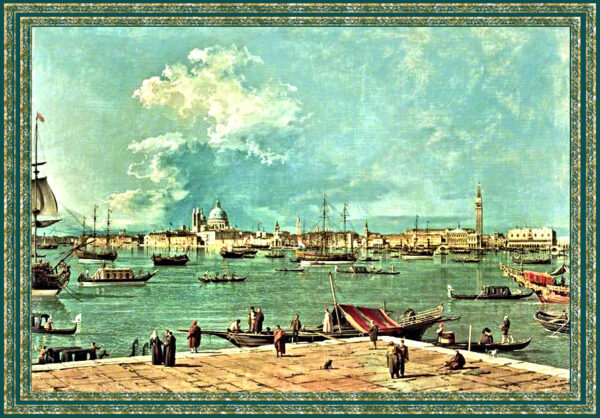

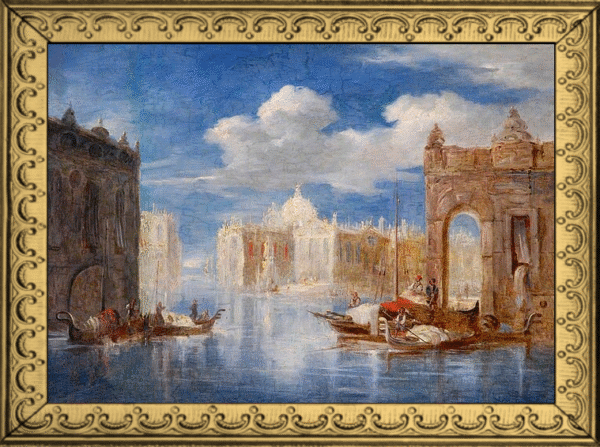

Here is Canaletto’s entrance to the Grand Canal. Santa Maria della Salute was built in gratitude for those spared from the devastating attacks of the plague in 1630. The church perches on the tip of an island. To the left lies the wide Giudecca Canal and Giudecca Island, a more working class neighborhood.

In the era when Venice ruled the Adriatic, it would awe visiting dignitaries by taking them to the Arsenale. There an entire warship would be constructed in one day. One day. The Venetians had the process perfected. Its labor force was specialized in a production line employing prefabricated parts. Its efficiency was not rivaled until the 20th century. It also produced weapons and needed supplies such as rope. It owned mainland forests which supplied the lumber.

I love the unusual composition of this view of Venice.

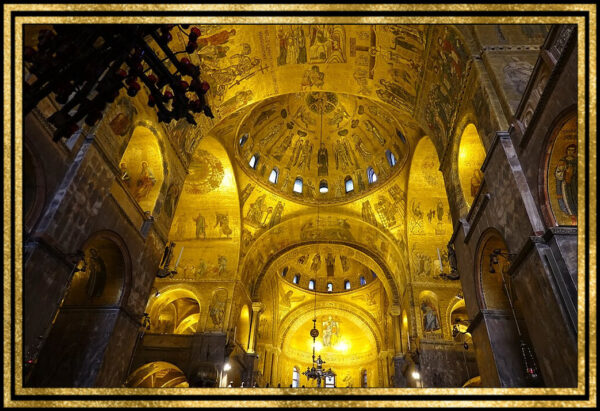

Like other great cities, she celebrated the fabulous domes of the great basilica of San Marco.

Equally fabulous within.

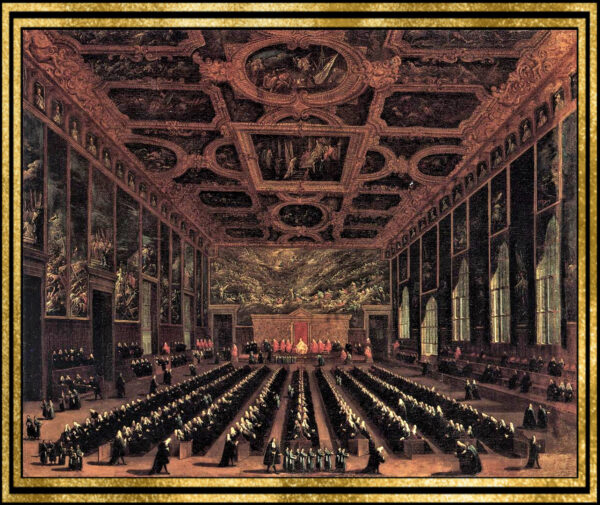

Venice also boasted the largest ceiling in Europe, the vast expanse of carving and paintings in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio within the Doge’s Palace. The meeting room was approximately 175 by 82 feet. Il Paradiso, by Tintoretto, is one of the largest paintings in the world. Up to 2,000 people gathered there.

Her churches were filled with great art by the Renaissance masters. The most celebrated today is Tintoretto, whose compositions are stunningly modern.

The Doge’s Palace suffered partial destruction from a great fire but was rebuilt respecting the beautiful Gothic style.

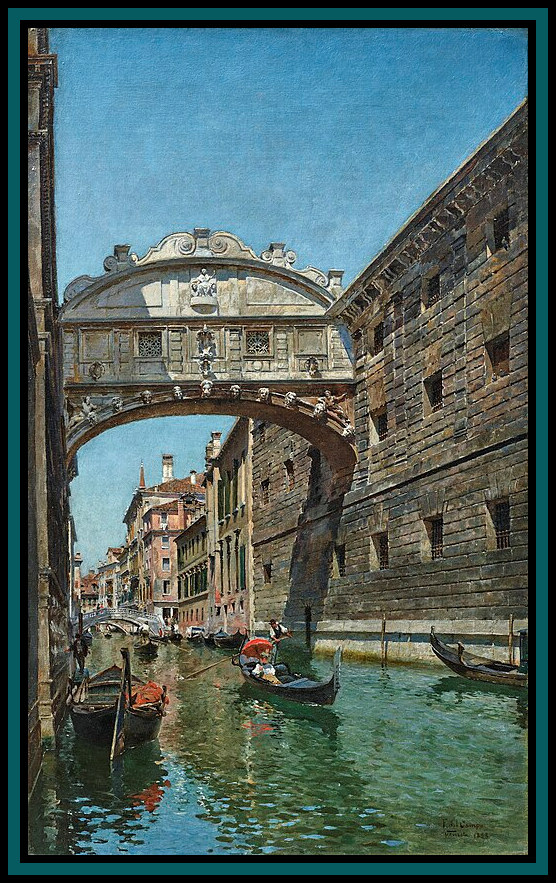

The name, The Bridge of Sighs conjures pining lovers, but it was the loss of freedom as prisoners crossed from judgment at the Ducal Palace to the hellish prisons where they often froze to death or died of heat stroke.

When new trade routes opened, almost overnight Venice became a has-been among nations it had nominated. Because of its beauty, it became a glorious tourist attraction instead. For centuries it celebrated Carnevale, often for much of the year. There were many traditional masks. Their meaning is part of a conversation in A Harmony of Hells.

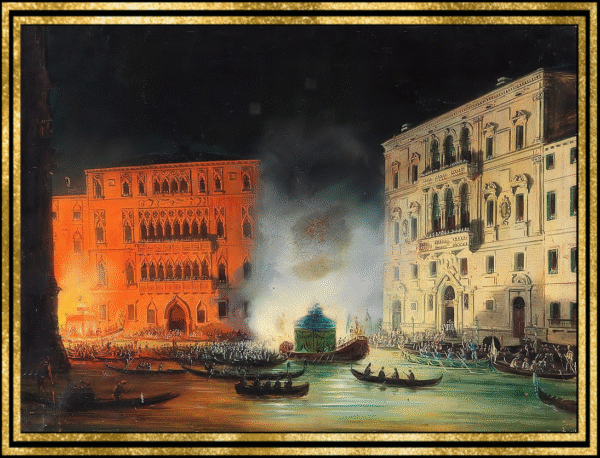

Venice became symbolic for romance, decadence, and mystery. Glorious during the day, it became haunting, often sinister at night.

Celebration was endless.

Sometimes gambling parties were held out on the lagoon.

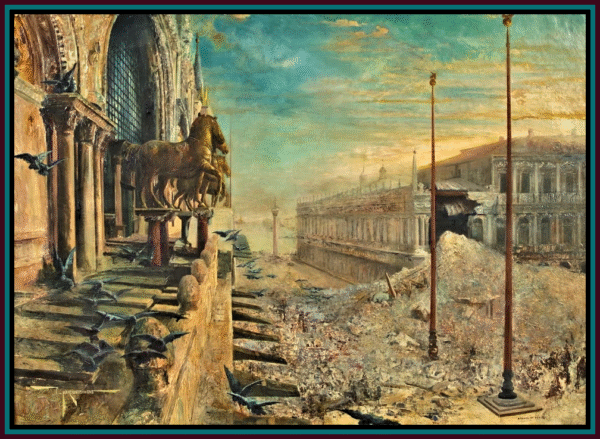

Venice was relatively untouched by war until the end of the 18th century, when the French and Austrians captured and traded her back and forth for decades, trampling her populace, destroying her navy and looting her art.

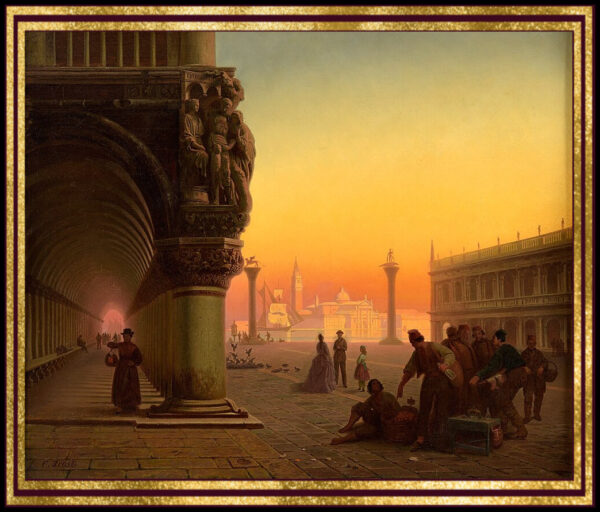

Napolean called the Piazza San Marco the drawing room of Europe.

He also stole her fabled bronze horses, though the Venetians had stolen them long ago from the Byzantines.

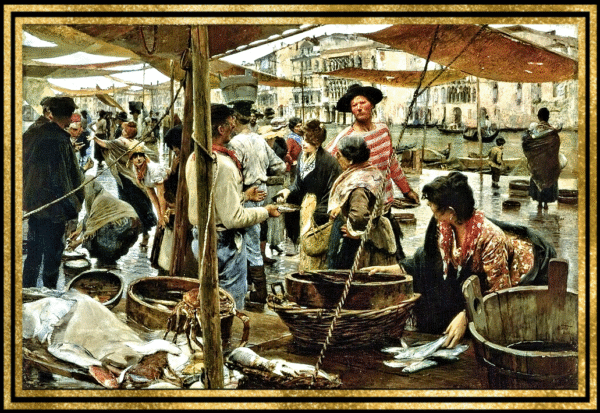

Eventually, Venice was free and Italy officially a country. Life returned to normal, though Venice was quite poor for a time.

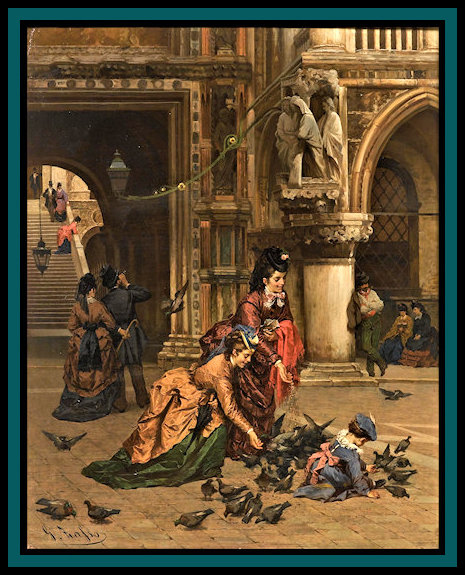

But the beauty of Venice proved irresistible, and tourists began to flock to the city.

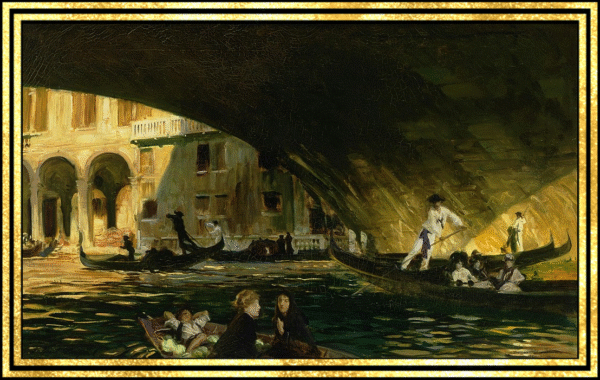

Much of the old magic of Venice remains in the gondolas. Tourists could ride in one back into the side canals and slip back a century or more, sunlight and shadow flickering on the walls. Here is a solitary lady in a gondola ride under the romanticized Bridge of Sighs.

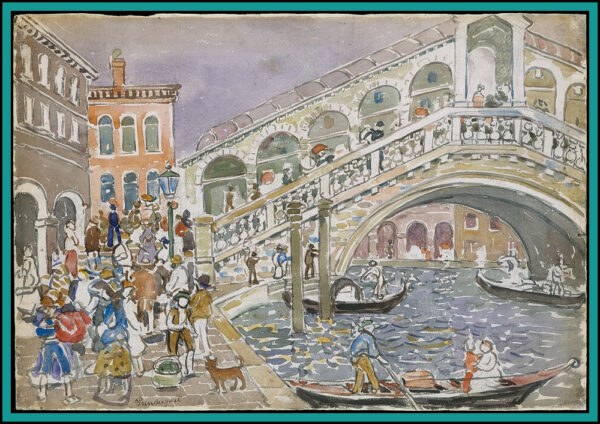

A visit to the shops on the Rialto Bridge was de rigueur.

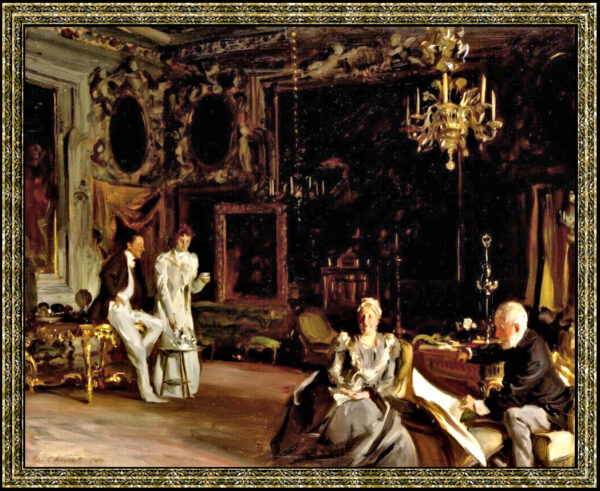

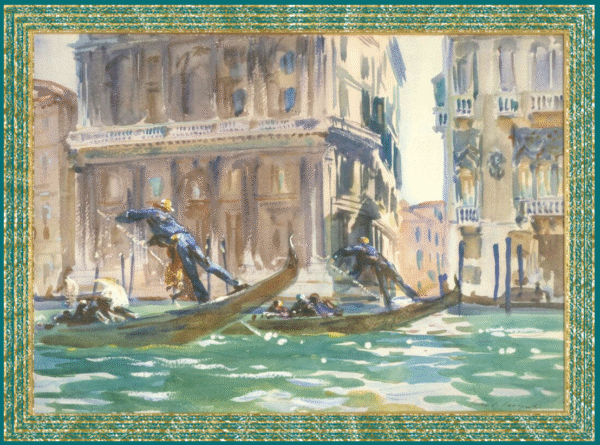

Writers like Henry James and Thomas Mann visited, as well as great artists, among them Turner, John Singer Sargent, and Whistler.

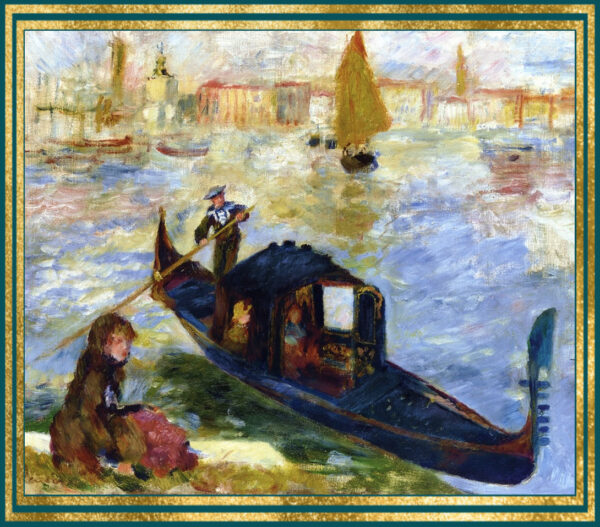

Many of the Impressionists visited Venice.

Gondolas were a favorite subject.

The base of the Campanile dates from the 9th century, when it was originally part of defensive fortifications. Later the belfry and spire were added, but the tower was subject to damage multiple times from earthquakes, lightning strikes and fires. In that era it was topped with a gold star which guided mariners. The tower was not finished until 1514 when the last flourishes were added, including a new topper, a weather vane spire in the form of the Archangel Gabriel. It was maintained that way for centuries.

In 1902 the Bell Tower collapsed, but there were no human fatalities.

Of course it was rebuilt in the next decade.

Carnevale also crumbled for a time. It was made illegal by the not very Holy Roman Emperor Francis II in 1797. Even when Venice was free of occupiers, she did not revive the city festival. Nonetheless, the rich gave fancy costume parties, and individuals and small groups would celebrate. This is the state of things when my characters visit the city. It was not until 1979 (nice little date reversal) that Venice decided Carnevale would be a great winter tourist attraction and the celebration has become a phenomenon.

Banner images by Bogolyulov and Frits Thaulow.

Click image below for the link to the CreativeCommons license for the bronze horses and Carnevale figures.