Other pages are devoted to Le Moulin Rouge and Le Moulin de la Galette. They were lynchpin cabarets in Montmartre and are visited in the first two novels. Here are two other cabarets with starring roles in A Harmony of Hells. And, beyond them, many other fascinating venues important in the era.

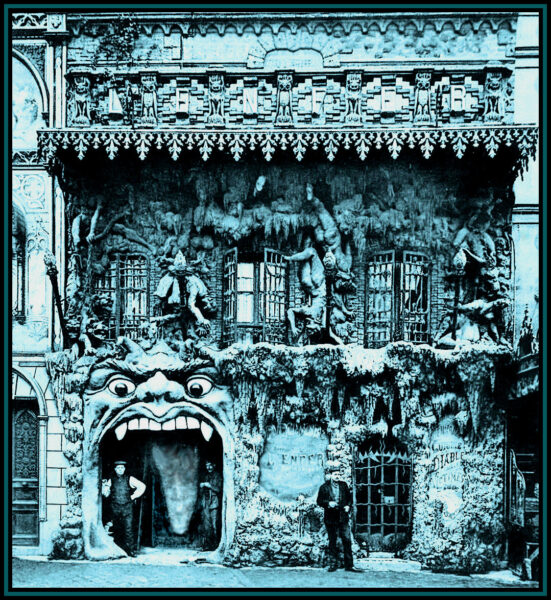

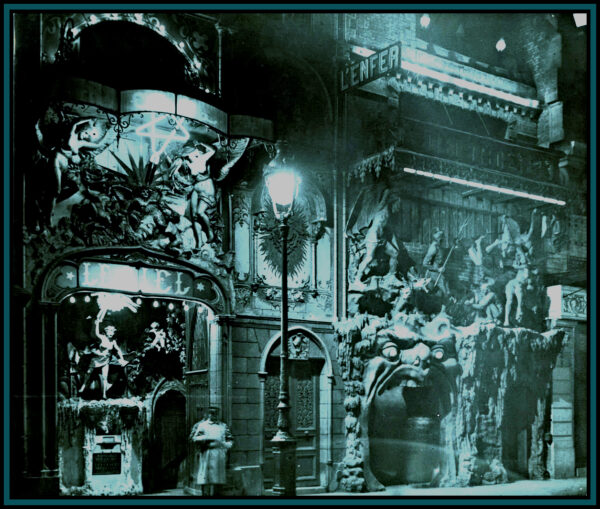

The first is the Cabaret de l’Enfer, Hell, where Averill Charron and Blaise Dancier meet for the first time.

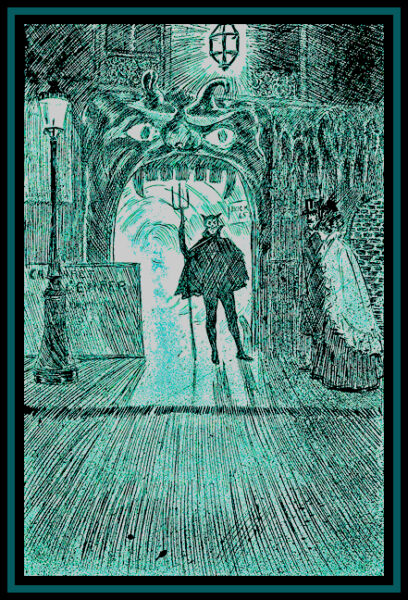

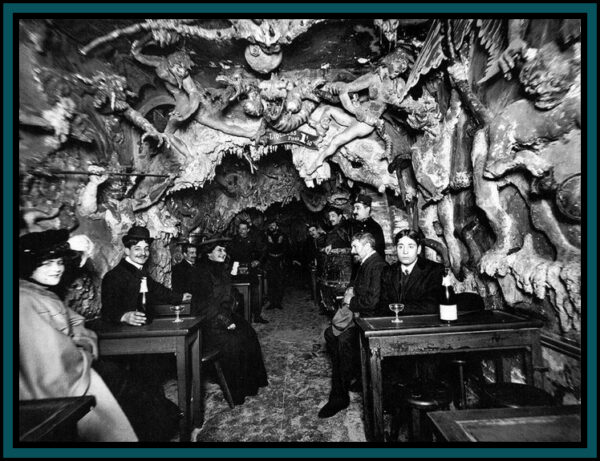

At night, patrons are greeted at the door by a demon or a Satanic figure. Inside, the sculptures of damned souls continue to writhe and crevices in the walls teem with various visual effects of fire, molten metals, and hissing puffs of sulfurous steam.

Numerous red tables stood against the fiery walls; at these sat the visitors… Instantly it became aglow with a mysterious light, which kept flaring up and disappearing in an erratic fashion; flames darted from the walls, fires crackled and roared.**

Blaise is very fond of a seething bumper of molten sins.

One of the imps came to take our order; it was for three coffees, black, with cognac; and this is how he shrieked the order: “Three seething bumpers of molten sins, with a dash of brimstone intensifier!” Then, when he had brought it, “This will season your intestines, and render them invulnerable, for a time at least, to the tortures of the melted iron that will be soon poured down your throats.” The glasses glowed with a phosphorescent light. “Three francs seventy-five, please, not counting me. Make it four francs. Thank you well. Remember that though hell is hot, there are cold drinks if you want them.”**

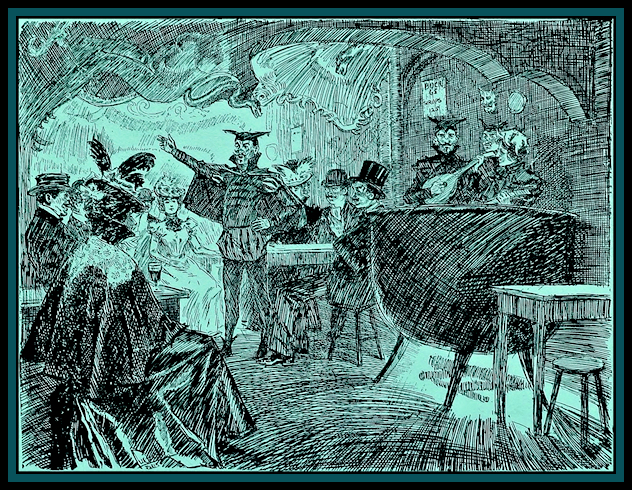

The Devil himself appears to provide torturous entertainment and promises of damnation.

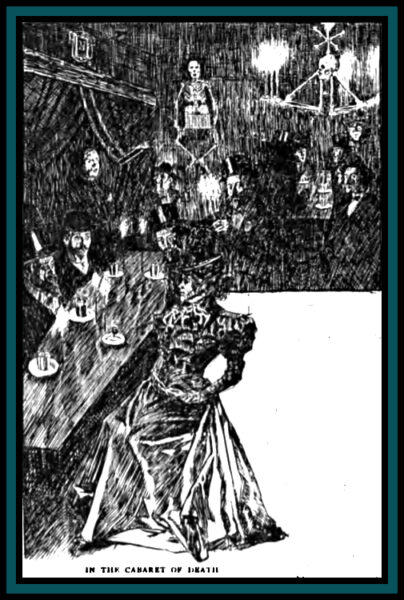

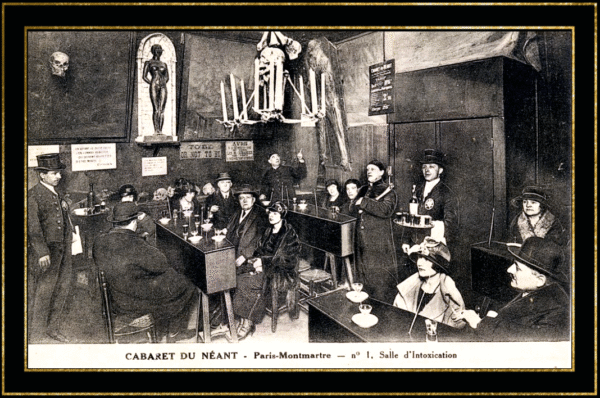

The Cabaret du Néant

First it was the Cabaret Philosophique in Brussels, then the Cabaret de la Mort (Death) in Paris. After the inconvenient death of a local, it was finally rechristened the Cabaret du Néant or the Cabaret of Nothingness.

It’s Salle d’Intoxication was staged with chandeliers of human bones suspended over tables shaped like coffins. Undertakers and monks waited on the patrons. The served serving drinks named after vile diseases, held inside skull-shaped cups.

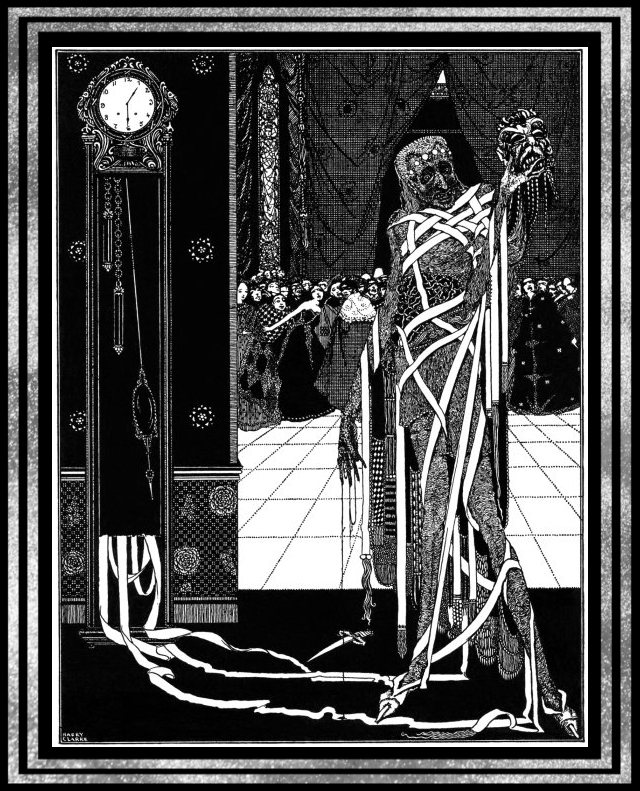

The occasional ghost would wander through the room. On the surrounding walls, paintings slowly mutated into scenes of carnage. Averill is feeling very bleak when he visits, though he has fond memories of an evolving painting based on Poe’s story, “The Mask of the Red Death.”

The occasional ghost would wander through the room. On the surrounding walls, paintings slowly mutated into scenes of carnage. Averill is feeling very bleak when he visits, though he has fond memories of an evolving painting based on Poe’s story, “The Mask of the Red Death.”

In a separate room, visitors were invited to watch a shrouded figure rot into a skeleton.

The Cabaret du Ciel

Next door to the red and black entrance to L’Enfer was the celestial blue and white facade of the Cabaret du Ciel, its heavenly counterpart.

Those who did not want to be seduced by demons could try their luck with angels, while harps play sweetly in the background.

“Presently we reached the gilded gates of Le Cabaret du Ciel. They were bathed in a cold blue light from above. Angels, gold-lined clouds, saints, sacred palms and plants, and other paraphernalia suggestive of the approach to St. Peter’s domain, filled all the available space about the entree. A bold white placard, “Bock, I Franc,” was displayed in the midst of it all. Dolorous church music sounded within, and the heavens were unrolled as a scroll in all their tinsel splendor as we entered to the bidding of an angel….

“A very long table covered with white extended the whole length of the chilly room, and seated at it, drinking, were scores of candidates for angelship, mortals like ourselves. Men and women were they, and though noisy and vivacious, they indulged in nothing like the abandon of the Boul’ Mich’ cafes. Gilded vases and candelabra, together with foamy bocks, somewhat relieved the dead whiteness of the table. The ceiling was an impressionistic rendering of blue sky, fleecy clouds, and golden stars, and the walls were made to represent the noble enclosure and golden gates of paradise.”

“Flitting about the room were many more angels, all in white robes and with sandals on their feet, and all wearing gauzy wings swaying from their shoulder-blades and brass halos above their yellow wigs. These were the waiters, the garcons of heaven, ready to take orders for drinks. “Two sparkling draughts of heaven’s own brew and one star-dazzler!” yelled our angel. “Thy will be done,” came the response from a hidden bar.”

Lapin Agile

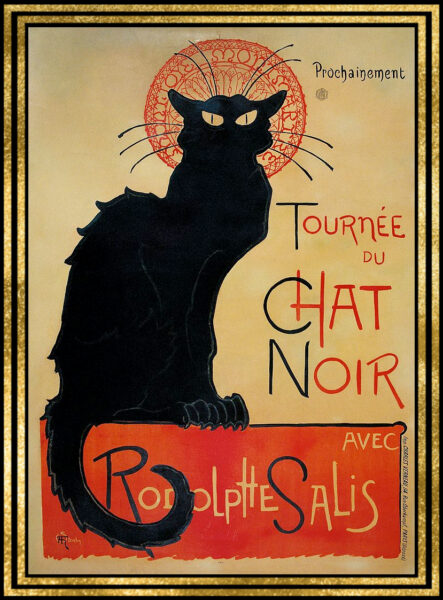

Le Cat Noir

The iconic Black Cat Cabaret poster by Théophile Steinlen can be found everywhere – though more in Montmartre than anywhere else.

Le Chat Noir may be the first modern cabaret, combining alcoholic drinks at tables with evening entertainment venues. It’s owner, Rodolphe Salis, was quite flamboyant, sporting vermillion hair and flashy floral waistcoats. Its arrival on the Left Bank was popularized by Les Hydropathes, a group of young artists and writers radical in their politics as well as their art, who claimed their fear of water meant they must drink only alcohol.

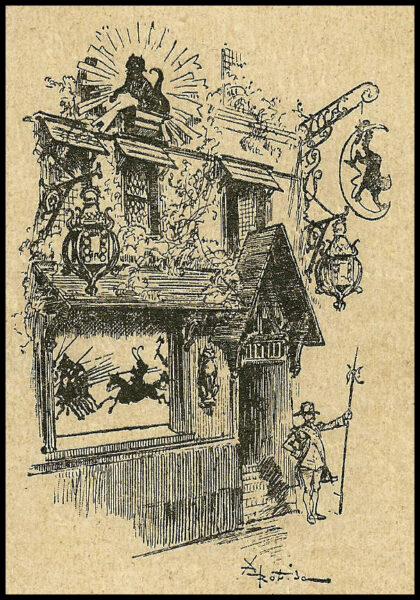

Here’s an etching of the exterior with the metal sign and a suggestion of the shadow plays in the window.

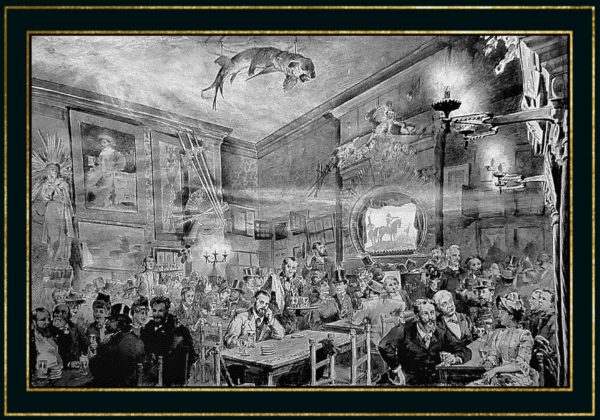

Although the cabaret began with live performances, it became famous for its illuminated shadow plays that played with color and special effects, as well as musical accompaniment. Artists like Adolphe Willette created these shows, starting with silhouettes created from cardboard and later from zinc. Salis would read stories of the shadow plays after the performance, or wander among the audience, encouraging or chastising them as needed.

Among the diverse patrons of Le Chat Noir were Jane Averil, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Claude Debussy and Eric Satie, Paul Verlaine and August Stringberg.