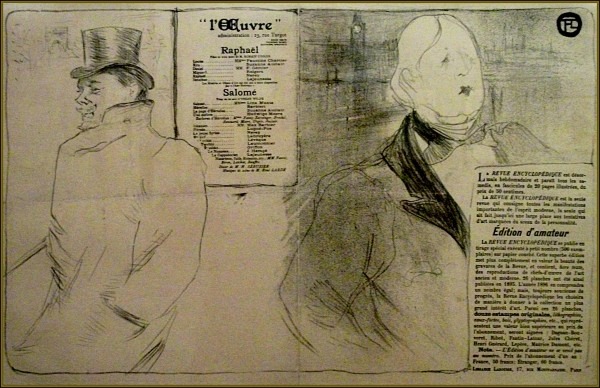

Theo’s cousin Averill is one of a group of young Parisian poets. They live and work all over the city of Paris, but Montmartre is their favorite haunt. Theo was with them the night they created their literary magazine, Le Revenant. The inspiration came after seeing the premiere of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, with its tale of obsessive passion ending in death.

Theo illustrated her cousin’s poems for Le Revenant. “A revenant is a ghost that is not only visible but tactile,” Averill had explained to her that night. “Sometimes even a corpse risen from the grave. A ghost that feeds upon emotion. Upon desire.” …from Floats the Dark Shadow

The poets thought that Salome would desire John the Baptist to reclaim his body and return to her as a revenant.

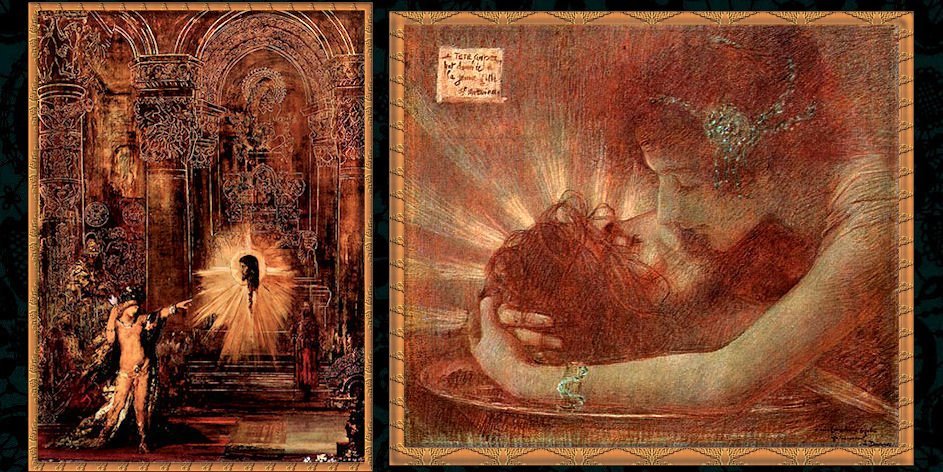

“In Gustave Moreau’s work … Des Esseintes at last saw realized the superhuman and exotic Salome of his dreams. She was no longer the mere performer who wrests a cry of desire and of passion from an old man by a perverted twisting of her loins; who destroys the energy and breaks the will of a king by trembling breasts and quivering belly. She became, in a sense, the symbolic deity of indestructible lust, the goddess of immortal Hysteria, of accursed Beauty, distinguished from all others by the catalepsy which stiffens her flesh and hardens her muscles; the monstrous Beast, indifferent, irresponsible, insensible, baneful, like the Helen of antiquity, fatal to all who approach her, all who behold her, all whom she touches.”

…from the John Howard translation of J. K. Huysmans A Rebours

Unlike many other literary magazines of the period, Le Revenant is based upon theme rather than style, though the group is primarily Symbolist in inspiration. Sharing a Catholic background, many of the poets incorporate Christian imagery; but they are also fascinated by the classic myths that haunt many artists of the period, ancient tales of Orpheus, Medusa, and Circe. I’ve asked each poet to pick a Salome painting, or other mythic image, to illustrate a poem they might write.

Averill is enamored of cruelty made exquisite in the intricate web of Gustav Moreau’s art, but he chose this image of the Cyclops because the figure of the woman reminded him of Theo.

Casimir chose Fra Lippo Lippi’s version of Salome dancing at King Herod’s feast. He liked that she seems innocent and oblivious of her mother’s intent as she dances, though her feet might be bathed in blood.

Jules was transfixed by this seductive Mary Magdelene by Goshka Datzov and would have nothing else.

Paul vacillated. He wanted the Salome by Lucas Cranach who projects the cold dominance of the power of wealth and privilege.

But he also admired Franz Von Stuck’s Judith who takes power into her own hands to destroy the threat to her people.

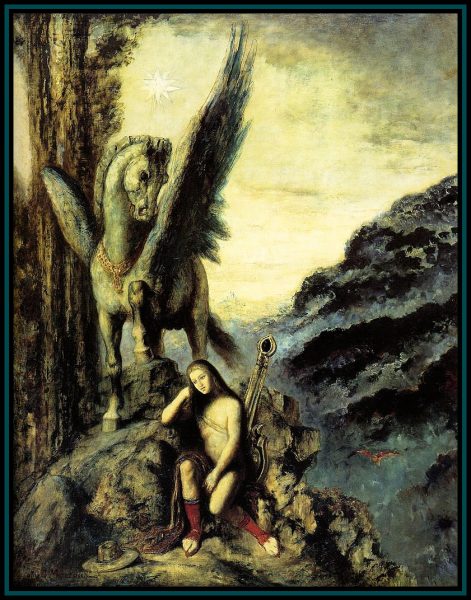

Theo was a bit impatient with the seductive, soul-devouring Salomes and such. I was going to have her chose one to copy, to practice her technique, but she declared she wanted a Pegasus. Then I couldn’t find one to satisfy her, but we settled on this Gustav Moreau painting, The Young Poet.

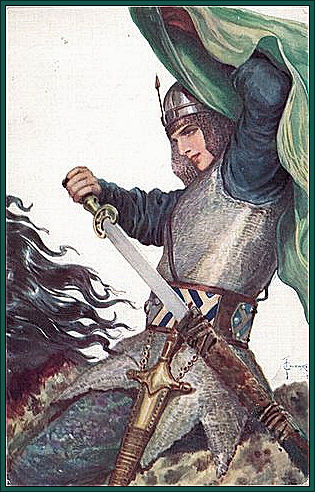

Because the Revenants call her their Amazone, those paintings were also searched and rejected, but this woman warrior by Sergey Solomko was her choice. She could be an Amazon, or even a Joan of Arc.

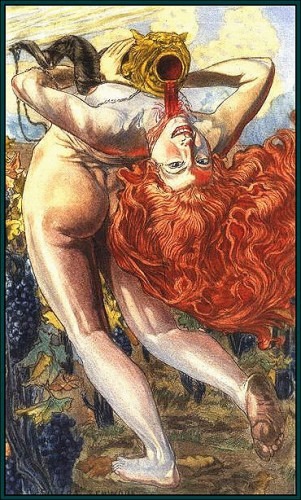

Then Theo found this illustration by Walter Crane that had the proper equine spirit she’d wanted in the Pegasus.

The Revenants were shaped by the revolutionary work of the last generation, by Gérard de Nerval, Stéphane Mallarmé, Rimbaud, and Verlaine. The were steeped in the poetry of Baudelaire and in his translations of the macabre visions of Edgar Allan Poe.

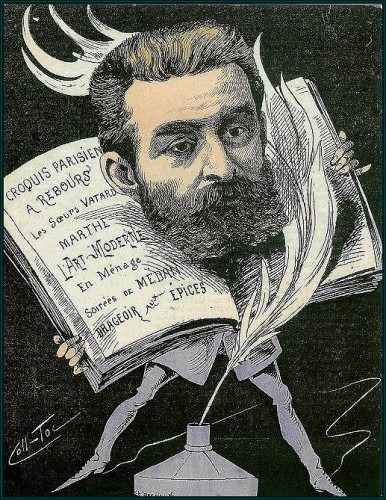

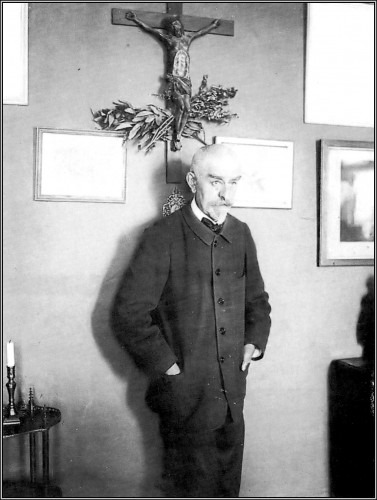

Also of great significance were the writings of the brilliant and eccentric J. K. Huysmans, a Parisian civil servant who began his career in the naturalistic style of Zola.

But even these works have a certain surreality. Huysmans continuted to evolve and became the premier decadent novelist with A Rebours (Against Nature or Against the Grain) the book which is said to have influenced Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Grey. Within that novel, A Rebours is referred to as the “yellow book”, which in turn became the inspiration for the decadent English periodical.

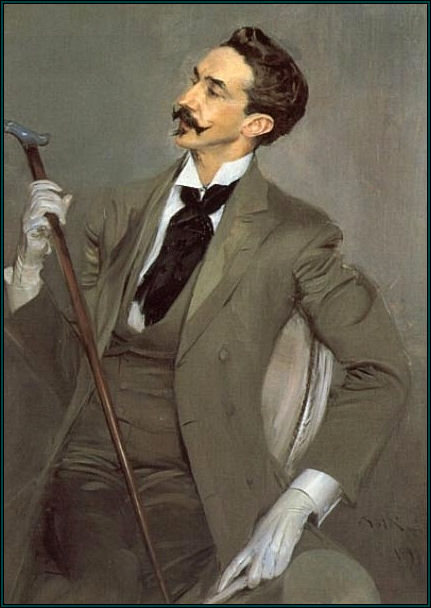

Des Esseintes, the aesthete protagonist of A Rebours was based on the Parisian aristocrat, poet, and ultimate dandy, the Count Robert de Montesquiou (later the Count was to inspire the character the Baron de Charlus in Proust’s A la Recherche du Temps Perdu).

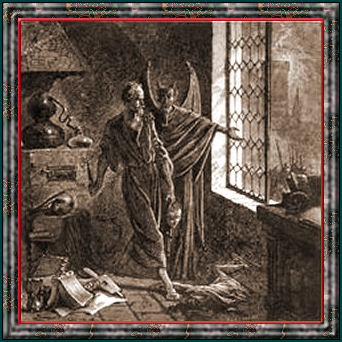

Here is an illustration depicting the infamous incident of the tortoise. A fictional and a real creature were destroyed by Des Esseintes and, before him, the Count.

“It did not budge at all and he tapped it. The animal was dead. Doubtless accustomed to a sedentary existence, to a humble life spent underneath its poor shell, it had been unable to support the dazzling luxury imposed on it, the rutilant cope with which it had been covered, the jewels with which its back had been paved, like a pyx.”

…A Rebours translation by John Howard

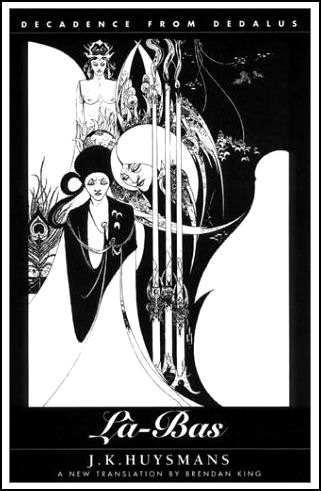

Five years later came Là Bas, the novel which proved even more shocking than A Rebours.

“It is a convoluted book. A novel about a novelist writing about Gilles de Rais’ ancient crimes. The narrator begins investigating medieval heresies and ends discovering an unbroken tradition of Satanism in France.”

“Là Bas,” Theo repeated. Down There. “All the way down to hell, from the sound of it.”

from Floats the Dark Shadow

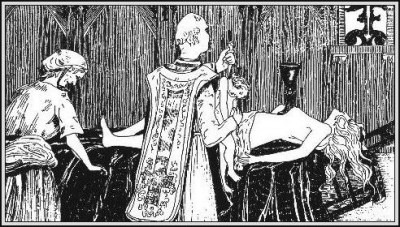

Messe Noire by Henry de Malvost

Messe Noire by Henry de Malvost

Là Bas stunned French readers with its depiction of a Black Mass in contemporary Paris.

“The canon solemnly knelt before the altar, then mounted the steps and began to say mass. Durtal saw then that he had nothing on beneath his sacrificial habit. His black socks and his flesh bulging over the garters, attached high up on his legs, were plainly visible. The chasuble had the shape of an ordinary chasuble but was of the dark red colour of dried blood, and in the middle, in a triangle around which was an embroidered border of colchicum, savin, sorrel, and spurge, was the figure of a black billy-goat presenting his horns.”

…from the Keene Wallace translation of Là Bas

Along with tales of bell ringing, the odd adulterous affair and a trip to a Black Mass, the disaffected novelist narrator of La Bas tells the story of Gilles de Laval, Baron de Rais. Before he was revealed as an infamous serial killer, the baron rode by the side of Jeanne d’Arc. For his valor and exploits in her service he was named a Marshal of France.

Perhaps the baron was already a murderer, or perhaps the loss of his inspiring heroine twisted his soul. He always claimed that his evil deeds rose from within.

For a time the wealthiest man in the kingdom, Gilles de Rais bankrupted himself with endless extravagances, both within his own castles and in elaborate public theatricals–one of which was a pagent to honor Jeanne. Vast portions of his riches went to alchemists and black magicians promising him a meeting with Satan.

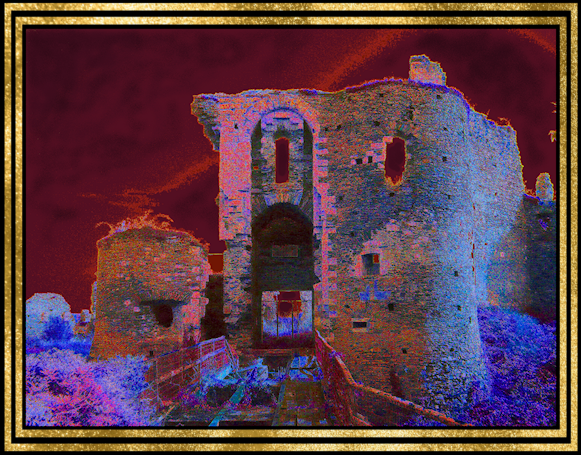

To lure the Devil or simply to satisfy his own perverse desires, Gilles sent his henchmen to lure or kidnap the children of the local peasants and brought them to one of his castles–Champtocé, Tiffauges, Machecoul–where he tortured and murdered them.

Champtocé, adapted from a photograph by Kormin”…the account of the investigation goes on, revealing hundreds of names, describing the grief of the mothers who interrogate passersby on the highway, and telling of the keening of the families from whose very homes children have been spirited away when the elders went to the fields to hoe or to sow the hemp. These phrases, like a desolate refrain, recur again and again, at the end of every deposition: ‘They were seen complaining dolorously,’ ‘Exceedingly they did lament.’ Wherever the bloodthirsty Gilles dwells the women weep.”

…from the Keene Wallace translation of Là Bas

At the trial, the suspected murders of these hundreds of children were disregarded until he could be accused and convicted of the far more heinous medieval crime of heresy. As an aristocrat, he was permitted the mercy of being throttled before his body was burned. His accomplices were less lucky.

“Far from his chàteaux, in his dungeon, alone, he had opened himself and viewed the cloaca which had so long been fed by the residual waters escaped from the abattoirs of Tiffauges and Méchecoul. He had sobbed in despair of ever draining this stagnant pool. And thunder-smitten by grace, in a cry of horror and joy, he had suddenly seen his soul overflow and sweep away the dank fen before a torrential current of prayer and ecstasy. The butcher of Sodom had destroyed himself, the companion of Jeanne d’Arc had reappeared, the mystic whose soul poured out to God, in bursts of adoration, in floods of tears.”

…from the Wallace translation of Là Bas

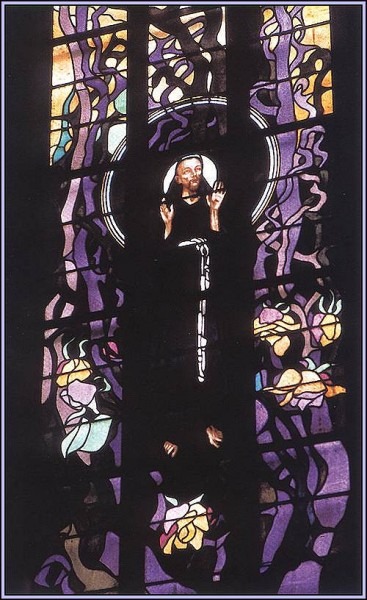

After the publication of Là Bas, Huysmans was told by his friend Barbey D’Aurevilly that he must needs choose ‘between the barrel of a revolver or the foot of the cross.’ So Huysmans turned toward the elusive light of salvation, struggling to reconcile his eternal cynicism with his longing for redemption and grace. His last books, En Route, Le Cathédrale, and L’Oblat, chronicle this journey. At the end of his life he embraced the suffering of his painful death from cancer.

The banner is composed of Orpheus and Eurydice by George Frederic Watts, Pain by Carlos Schwabe, and Mystery by Xavier Mellery.